Title: The Discworld Companion

Title: The Discworld Companion

Author(s): Terry Pratchett, Stephen Briggs

Release year: 1994

Publisher: Victor Gollancz

Why in Database: As in all “Companions” from the Discworld, also in the first one there was a lot of turtle fragments. Below we show probably all the elements with turtle mentions, text or visual.

First one is in Turtles All the Way text, before the main section with encyclopedic entries:

Anyway, we seem to have a turtle-shaped hole in our consciousness. On every continent where turtles grow, early man looked at the things sunning themselves on a log (or disappearing with a ‘plop’ into the water at the shambling approach) and somehow formed the idea that a large version of one of these carries his world on its back.

Priests came along later and in order to justify their expenses added little extras, like world-circling snakes and huge elephants, and some time later the idea grew that the world was not round and flat but more like an upturned saucer. The basic idea, though, was turtles all the way. Why turtles is a mystery but turtles it was, in Africa, in Australia, in Asia, in North America.

Perhaps much modern malaise can be traced to a deep-seated ancestral fear that, at any moment, the whole thing will go ‘plop’.

I came across the myth in some astronomy book when I was about nine. In those white-heat-of-technology days every astronomy book had an early chapter which was invisibly entitled ‘Let’s have a good laugh at the beliefs of those old farts in togas’ (reality in those days being something called Zeta, a nuclear reactor that would soon be producing so much electricity we’d be paid to use it). And there was the Discworld, more or less. The image remained with me – possibly lodging that turtle-shaped hole – and trotted forward for inspection much later when I needed it.

In the entry Astrolabe

Astrolabe. One of the Disc’s finest astrolabes is kept in a large, star-filled room in KRULL. It includes the entire Great A’Tuin-Elephant-Disc system wrought in brass and picked out with tiny jewels.

Around it the stars and planets wheel on fine silver wires. On the walls the constellations have been made of tiny phosphorescent seed pearls set out on vast tapestries of jet-black velvet. These were, of course, the constellations current at the time of the room’s decoration – several would be unrecognisable now owing to the Turtle’s movement through space. The planets are minor bodies of rock picked up and sometimes discarded by the system as it moves through space, and seem to have no other role in Discworld astronomy or astrology than to be considered a bloody nuisance.

In the entry Astrozoologists

Astrozoologists. Krullian scientists interested in studying the nature of the Great A’TUIN. Specifically, its sex.

In the entry A’Tuin, the Great

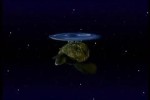

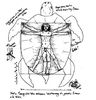

A’Tuin, the Great. The star turtle who carries the Discworld on its back. Ten-thousand-mile-long member of the species Chelys galactica, and the only turtle ever to feature on the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram. Almost as big as the Disc it carries. Sex unknown.

Shell-frosted with frozen methane, pitted with meteor craters and scoured with asteroidal dust, its eyes are like ancient seas, crusted with rheum. Its brain is the size of a continent, through which thoughts move like glittering glaciers.

It is as large as worlds. As patient as a brick. Great A’Tuin is the only creature in the entire universe that knows exactly where it is going.

Upon its back stand Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen, the four giant elephants upon whose shoulders the disc of the world rests. A tiny sun and moon spin around them on a complicated orbit to induce seasons, although probably nowhere else in the multiverse is it sometimes necessary for an elephant to cock its leg to allow the sun to go past.

After the events of The Light Fantastic, the Great A’Tuin was orbited by eight baby turtles, each with four small world-elephant calves and tiny discworlds, covered in smoke and volcanoes. They have subsequently begun their own cosmic journeys.

Wizards have tried to tune into Great A’Tuin’s mind. They trained up on tortoises and giant sea turtles to get the hang of the Chelonian mind. But although they knew that the Great A’Tuin’s mind would be big, they rather foolishly hadn’t realised it would be slow. After thirty years all they found out was that the Great A’Tuin was looking forward to something.

People have asked: How does the Disc move on the shoulders of the elephants? What does the Turtle eat? One may as well ask: What kind of smell has yellow got? It is how things are.

In the entry Brutha

(…) When the Great God OM was trapped in the form of a tortoise, Brutha – whose quiet and unquestioning belief meant he was the only person left in the entire country who could hear the god speak – carried him round in a wickerwork box slung over his shoulder.

In the entry Calendars

Calendars (The discworld year). The calendar on a planet which is flat and revolves on the back of four giants elephants is always difficult to establish.

It can be derived, though, by starting with the fact that the spin year – defined by the time taken for a point on the Rim to turn one full circle – is about 800 days long. The tiny sun orbits in a fairly flat ellipse, being rather closer to the surface of the disc at the rim than at the Hub (thus making the Hub rather cooler than the rim). This ellipse is stable and stationary with respect to the Turtle – the sun passes between two of the elephants.

In the entry Caroc cards

Caroc cards. Distilled wisdom of the Ancients. Deck of cards used on the Discworld for fortune telling and for card games (see CRIPPLE MR ONION). Cards named in the Discworld canon include The Star, The Importance of Washing the Hands (Temperance), The Moon, The Dome of the Sky, The Pool of Night (the Moon), Death, the Eight of Octograms, the Four of Elephants, the Ace of Turtles.

In the entry Chimera

Chimera. A desert creature, with the legs of a mermaid, the hair of a tortoise, the teeth of a fowl, the wings of a snake, the breath of a furnace and the temperament of a rubber balloon in a hurricane. Clearly a magical remnant. It is not known whether chimera breed and, if so, with what.

In the entry Chelonauts

Chelonauts. Men who journey – or at least intend to journey – below the Rim to explore the mysteries of the Great A’TUIN. Their suits are of fine white leather, hung about with straps and brass nozzles and other unfamiliar and suspicious contrivances. The leggings end in high, thick-soled boots, and the arms are shoved into big supple gauntlets. Topping it all is a big copper helmet designed to fit on the heavy collars around the neck of the suits. The helmet has a crest of white feathers on top and a little glass window in front.

In the entry Death, House of

(…) In one corner and dominating the room, however, is a large disc of the world. This magnificent feature is complete down to solid silver elephants standing on the back of a Great A’TUIN cast in bronze and more than a metre long. The rivers are picked out in veins of jade, the deserts are powdered diamonds and the most notable cities are picked out in precious stones.(…)”

In the entry Discworld, the.

(…) And there, below the mines and sea-ooze and fake fossil bones put there (most people believe) by a Creator with nothing better to do than upset archaeologists and give them silly ideas, is Great A’TUIN.

(…)

The Discworld should not exist. Flatness is not a natural state for a planet. Turtles should grow only so big. (…)

In the entry Gamblers’ Guild

Gamblers’ Guild. Motto: EXCRETVS EX FORTVNA. (Loosely speaking: ‘Really Out of Luck’.) Coat of arms: A shield, gyronny. On its panels, turnwise from upper sinister: a sabre or on a field sable; an octagon gules et argent on a field azure; a tortue vert on a field sable; an ‘A’ couronnée on a field argent; a sceptre d’or on a field sable, a calice or on a field azure; a piece argent on a field gules; an elephant gris on a field argent. (…)

In the entry Granny’s Cottage

On the bed itself is a patchwork quilt which looks like a flat tortoise. It was made by Gordo SMITH and was given to Miss Weatherwax by ESK’S mother one HOGSWATCHNIGHT.

In the entry Krull

(…) The Krullians once had plans to lower a vessel over the Edge to ascertain the sex of the Great A’TUIN.

In the entry Morecombe

Morecombe. A vampire. The solicitor of the RAMKIN family. Scrawny, like a tortoise; very pale, with pearly, dead eyes.

In the entry Om

Om. The Great God Om. He has a vast church in Kom, OMNIA. When he is first encountered, he is a small tortoise with one beady eye and a badly chipped shell. (…)

In the entry Potent Voyager

Potent Voyager. Vessel constructed by DACTYLOS to take two chelonauts out over the Rim to determine the sex of the Great A’TUIN. A huge bronze space ship, without any motive power other than the ability to drop.

In the entry Rimbow

(…) The Rimbow hangs in the mists just beyond the edge of the world, appearing only at morning and evening when the light of the Disc’s little orbiting sun shines past the massive bulk of the Great A’TUIN and strikes the Disc’s magical field at exactly the right angle.

In the entry Simony, Sergeant

Simony, Sergeant. Sergeant in the Divine Legion in OMNIA and a follower of the Turtle Movement.(…)

In the entry Turtle, the Great.

Turtle, the Great. (See A’TUIN, GREAT.)

In the entry Turtle Movement

Turtle Movement. A secret society in OMNIA which believes that the Disc is flat and is carried through space on the backs of four elephants and a giant turtle. Their secret recognition saying is ‘The Turtle Moves’. Their secret sign is a left-hand fist with the right hand, palm extended, brought down on it. Most of the senior officials of the Omnian church are members of the ‘movement’, but since they all wear hoods and are sworn to absolute secrecy each thinks he is the only one.

In the entry Zodiac

It would be more correct to say that there are always sixty-four signs in the Discworld zodiac but also that these are subject to change. Stars immediately ahead of the Turtle’s line of flight change their position only very gradually, as do the ones aft. The ones at right angles, however, may easily alter their relative positions in the lifetime of the average person, so there is a constant need for an updating of the Zodiac. This is done for the STO PLAINS by Unseen University, but communications with distant continents (who in any case have their own interpretations of the apparent shapes in the sky) are so slow that by the time any constellation is known Discwide it has already gone past.

Turtle elements were also found in the texts at the end of the book, after the encyclopedic part.

There are two turtle fragments in “A Brief History of Discworld”:

Pratchett still remained, though, a best-known unknown author. All across the country parents were curious to see what it was their children found so amusing; in offices people would tell bemused colleagues: Look, there’s this world on the back of a giant turtle, and Death rides a white horse called Binky and look, I’ll loan you this copy, all right?’

The world itself is absurd. It is flat and round and rests on the back of four elephants, which are themselves carried through space on the back of a giant turtle. It just happens also to be firmly rooted in our planetary mythology. It is a subset of one of the great world myths, found in Australia before Cook, and North America before Columbus and in Bantu legend. The human race appears predisposed to believe that the world is flat and rides on a turtle.

One in “All the Stage’s a World…”:

A flat, circular world borne through space on the backs of four enormous elephants who themselves stand on the carapace of a cosmically large turtle? Nothing to it.

And also ine in “Terry Pratchett: The Definitive Interview”:

I know you get asked this all the time, but we still have to ask it here . . . In your own words, where did Discworld come from?

I used to say that the basic myth that the world is flat and goes through space on the back of a turtle is found on all continents – some school kids recently sent me a version of it I hadn’t run across before. And once you get into Indo-European mythology you get the elephants, too. But I’ve got asked so many times, and no one listens anyway, so now I just say I made it up.

Author: XYuriTT