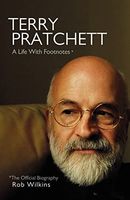

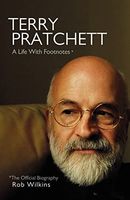

Title: Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes

Title: Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes

Author(s): Rob Wilkins

Release year: 2022

Publisher: Transworld

Why in Database: Terry Pratchett’s biography, written by his longtime assistant, Rob Wilkins. He was the author of the series about Discworld, so of course, there are some mentions of turtles – although much more about real tortoises raised by Pratchett than the big space turtle, A’Tuin.

During an average working week in the Chapel, a vast amount of writing would get done, yet somehow, while the work was percolating in Terry’s mind, there also seemed to be plenty of time for activities that could only be filed under A for ‘Arsing Around’. There were, for example, the days spent devising ever more intricate and unnecessary ways to automate the office. There were the hours passed feeding the tortoises, or up at the local garden centre.

Terry shared the family home with, at various times, an almost entirely brainless spaniel, a tortoise named Pheidippides, after the original marathon runner, and a budgerigar called Chhota, but no further small Pratchetts joined them.

I go out to my car, extremely puzzled, and also quite worried. Have I done something wrong? Have I messed up somewhere? Have I misfiled something, or accidentally thrown something away? What’s my offence here? Have I been less than suitably subordinate to Patch, the office cat, also known as ‘the HR Department’? Have I run over one of the tortoises without realizing, driving in that morning? What the hell is it?

But that degree of separation didn’t seem to make either Lyn or him particularly happy, so in due course they found a flat to rent cheaply on the ground floor of an Edwardian house on Amersham Hill in High Wycombe, moving in along with a growing collection of tortoises, who also commuted.

The tortoises were Terry’s fault: he had discovered that he could not see a tortoise without forming the urge to ‘rescue’ it. This first happened in a pet shop in the Frogmore district of High Wycombe, and would happen in several other pet shops thereafter until the collection of rescued tortoises stood at around ten – some of the Mediterranean breed, some spur-thighed. Years later, Terry would still be prone to this rescuing urge. On tour in Glasgow in the 1990s, he released a tortoise soon to be known as Big Spotty from its captivity in a city centre pet shop – and was then appalled when someone at the airport told him he couldn’t board his plane with it*. ‘You can’t stop me,’ Terry said, rather grandly. ‘This is Great Britain.’ Big Spotty flew with Terry to Southampton.

Under this new commuting arrangement, Lyn found clerical work in High Wycombe. The pair of them would do their jobs all week and then on Friday, which was the slow day, post-publication, at the Bucks Free Press, Terry would try to get away early, and they would box up the tortoises, load them into the Morris van and head for the west country, mostly by the back roads and with a stop for fish and chips in Marlborough where, according to Terry, ‘the chippy was particularly good.’ They would split their life in this way for eighteen months.

One of the footnotes:

These were the days, clearly, before the invention of the ‘emotional support tortoise’. Carrying land-dwelling reptiles onto aircraft is presumably a far simpler project now.

Następny fragment znów dotyczy kręcących się po włościach żółwi:

Wine bottles stood fermenting around the gas fire in the sitting room, just behind the tortoises in the priority queue for warmth and with Terry and Lyn forming a third, outer ring beyond that.

If only there was a job Terry could find in which he felt as comfortable as he did at the Bucks Free Press, but which was within reach of Rowberrow and which didn’t force him, Lyn and the tortoises to take their chances each weekend with the Friday night traffic on Marlow Hill. If he could find the right job in the west country, then surely everything would be perfect.

There were cats and there were tortoises, of course – and sometimes, when slippers were left to warm by the open fire, the tortoises would spot an opportunity and crawl into them. More dangerously, the tortoises might even creep at night into the fire’s still-warm embers, so you had to be careful, when you re-lit the fire in the morning, that you weren’t accidentally using a tortoise for kindling. According to Lyn, there was at least one occasion when a tortoise had to be urgently run under the cold tap in the kitchen.

One of the footnotes:

Ringworld, a torus, a million miles wide, surrounding a star rather than orbiting it, clearly feeds into Discworld, albeit without the supporting elephants and turtle. Terry and Larry Niven met some years later and got along well. Niven seemed to regard Strata as a homage to his work, and Terry afterwards described Niven to Dave Busby as resembling ‘a small, stuffed owl’, which was by no means necessarily a pejorative description in Terry’s hands.

It’s safe to say that, during Lyn and Terry’s first decade in Rowberrow, activities such as wool-spinning, cheese-making, beekeeping and tortoiseraising took precedence over watching the television.

Colin Smythe Limited brought out the hardback of The Colour of Magic in November 1983. ‘In a distant and second-hand set of dimensions, in an astral plane that was never meant to fly, the curling star-mists waver and part …’ And here in public for the first time was Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, a flat planet borne through space on the backs of four elephants – Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen – who are themselves positioned on the back of the giant star turtle Great A’Tuin, an arrangement quietly borrowed by Terry from Indian mythology* and which was somehow fundamental to what went on in the book and, at the same time, almost completely beside the point. The Colour of Magic introduced the inept wizard Rincewind, and Twoflower the tourist, and the Luggage, and the concept of Octarine, the eighth colour of the Discworld spectrum, visible only to wizards and cats. It also introduced the concept of being spectacularly funny in a Fantasy novel. And it was spectacularly funny because its real subject, in the end, wasn’t elephants or astronomically huge turtles or wizards, nor even cats, but human foibles, which its author clearly, even though he was still honing his craft, had found a unique way to expose and articulate.

Ponownie kawałek z przypisu, o obecności żółwi w mitologii:

‘I filched it,’ as Terry wrote, ‘and ran away before the alarms went off.’ Indian mythology may merely have been the place where the world-on-a-turtle image was most prominent. Terry’s further explorations indicated that practically every mythology you could find had a soft spot at some time in its life for turtles flying through space. And why not?

There would be plenty of scope for chickens and vegetables and fruit and tortoises and owl boxes, and also sheep.

At the same time, Great A’Tuin, the elephants, the Disc, the oceans flowing off the rim… you could see how it might work.

After about 20 minutes, the back door crashed open in a blast of cold, damp air. In came Terry in a full-length brown leather duster coat and a battered hat, entirely soaked and very bedraggled. He had been feeding the tortoises.

Terry had this idea for a Discworld novel with the working title ‘The Turtle Stops’. Great A’Tuin, the star turtle bearing the Disc, was going to become unwell. This would lead to an exploratory journey into the turtle, in preparation for which Terry had, needless to say, consulted a zoologist that he knew, John Chitty BVetMed Cert ZooMed CBiol MSB MRCVS, no less, in order to determine what, exactly, you would find if you ever ventured inside a turtle. But the pressing issue now was, how would the wizards of Unseen University come to know that Great A’Tuin was sick? We batted it back and forth between us in the office and then, that lunchtime, in the pub. Would there maybe be magical vibrations of some kind, which the wizards would be able to pick up? No. Too easy. Too close to Dr Who’s sonic screwdriver: not a proper solution.

So, what if, Terry suggested, it was possible to observe the slowing of the turtle’s interstellar paddling motion, from somewhere very high on the Disc?

This seemed problematic to me.

‘Terry, there would be nowhere on the Disc from which this phenomenon was visible.’

Terry was insistent. ‘Why not? They could sit on top of the Tower of Art, with a telescope.’

‘No, even then, they wouldn’t be in a position to see Great A’Tuin.’

‘Yes, they would,’ said Terry. ‘It’s the tallest building on the Disc!’

‘But it still wouldn’t be tall enough,’ I said. ‘It simply doesn’t work.’

In order to make my point, I grabbed a plate with the remainder of my lunch on it, balanced it on my fingertips and held it up between us.

‘OK, so my hand is the turtle, the plate is the Disc, the pea on the plate is the tower. There is no way that anyone standing on that pea is going to be in a position to see my hand under the plate.’

On the way back, Terry makes an unannounced detour to the greenhouse and attends to the tortoises for a while.

At some point after midnight, following a day of gaming and dealing with tortoises and fiddling about in the greenhouse and stomping around at the garden centre, Terry has laid down this concluding passage, perfectly answering the brief.

It was the same when we were writing a passage towards what would have become The Turtle Stops and needed to take the reader inside Great A’Tuin.

‘Terry, we’re inside the star turtle. What do we see?’

‘It’s as big as a cathedral.’

‘Bigger, surely …’

‘It’s as big as a city.’

‘Bigger than that, too, surely …’

Which is deeply saddening, of course. All those books he never got to write! All those books we never got to read! How many of them might there have been? Several were already underway: ‘Raising Taxes’; ‘Running Water’; ‘The Turtle Stops’; a second volume of adventures for the Amazing Maurice; ‘What Dodger Did Next’;

Author: XYuriTT

Title: Gamera: Rebirth

Title: Gamera: Rebirth

Title: Star Wars Jedi: Survivor

Title: Star Wars Jedi: Survivor

Title: Strange World

Title: Strange World

Title:The Mandalorian

Title:The Mandalorian

Title: The Whole Hog: Making Terry Pratchett’s ‘Hogfather’

Title: The Whole Hog: Making Terry Pratchett’s ‘Hogfather’