Title: The Blue Planet. A natural History of the Oceans

Title: The Blue Planet. A natural History of the Oceans

Author(s): Andrew Byatt, Alastair Fothergill, Martha Holmes

<Release year: 2001

Publisher: BBC Books

Why in Database: This book is a kind of supplement, complementary material to the TV nature series Blue Planet. There are many fragments about turtles, one huge (~3 pages), one smaller (one “frame”) and a lot of tiny mentions. We cite all such pieces.

The first mention is about laying eggs and coordinating of that with the tides:

Olive ridley turtles also seem to coordinate their egg-laying with the tidal cycle. On just a few nights each year, tens of thousands of females emerge together on just a few beaches worldwide in a breeding spectacle called an arribada. These arribadas always start when the moon is in first or last qurter. This is the time of neap tides, when the sea tends to be calmer and more of the beach remains exposed, making egg-laying easier.

The second mention is about Ghost Crabs, that sometimes eat baby turtles:

they will eat practically anything, and will even grab unfortunate turtle hatchlings down indo their burrows.

The next piece deals with how black vultures benefit from access to turtle eggs:

In Costa Rica the mass nesting of thousands of Olive Ridley turtles supports hundreds of black vultures which patrol the beach each morning. As the rising tide washes turtle eggs out of the sand, the vultures snap them up.

Another mention is a brief note that sea turtles must lay their eggs on the mainland:

The ancestors of today’s sea turtles were originally land-based reptiles, and as they still lay eggs with shells, they have no option but to deposit them on dry land.

The following excerpt is the longest fragments in the book about turtles, extending over three pages and introducing many facts about them:

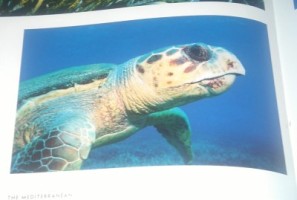

REPTILES RETURN

The tiny island of Ascension, which lies in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, is just it km (7 miles) wide. While most of it is an inhospitable volcanic wasteland, it has a few sandy beaches that provide the only nesting sites for thousands of green turtles. These creatures, who spend most of their lives in a solitary pursuit of food along the coast of Brazil, make an annual 2400 km (1500 mile) migration out into the Atlantic Ocean. Exactly how they navigate their way to the tiny pinprick of rock that is Ascension still remains something of a mystery. However, year after year the females return to exactly the same rookery at which they themselves were hatched.

A safe place for the eggs

Sea turtles produce the soft, leathery eggs typical of most reptiles. As they evolved on land, they are not able to withstand the rigours of salt water, so they must be laid on land where the warmth of the sand incubates them. The traditional nesting beaches are known as rookeries, but why particular beaches are favoured is far from clear. It may be that current nesting choices reflect historic patterns that have existed for hundreds or thousands of years. Many suitable beaches may now be untouched simply because the local turtle population has been over-exploited or disturbed by man. Certainly tagging experiments and DNA analysis have shown that females not only return to the same beach every year, but, typically emerge within a few hundred metres of where they last nested. A perfect nesting beach for sea turtles needs to have open-water access, it must be free from the risks of flooding by tide or ground water and the sand must be just the right consistency for egg-laying. Too soft and it is almost impossible for the female to dig a nesting burrow without it collapsing. Too solid and there is not enough air for the incubating eggs. Gathering off the rookeries to mate after weeks or even months of migration, the females are sexually receptive for just one week. During this time they may be inseminated by several males, who are sexually active for about a month. At the end of this courtship period, the males return home, but the females will remain for months. Using stored sperm, they fertilize the eggs inside their body, then wait offshore for about two weeks until they are ready to lay. They then haul themselves on to the beach. Within minutes of leaving their natural habit, the turtles are exhausted by the struggles of returning to land. Their eyes clog with sand and every metre up the beach seems an effort. The final challenge is digging a hole in the sand and laying about 120 eggs within it. Just two weeks later, the ordeal must be repeated to lay another clutch of eggs. This process continues throughout the breeding season, with some turtles laying up to 11 clutches.

During the long months at the rookeries,th females spend little time feeding, living instead off their reserves of fat stored up before the migration began. They are unlikely to return the following year. It will be between two and eight years before this particular set of females undertake the breeding migration again.

The hatchlings emerge

Incubation of the eggs normally takes about eight weeks, but the temperature of the sand determines the speed with which the embryos develop. As turtles have no sex-determining chromosomes, temperature also determines the sex of the hatchlings. Below 28 °C (82°F) and almost all the hatchlings will be male. Above 30.5 °C (87 °F) and nearly all the hatch-lings will be female.

Once they emerge from the eggs, the baby turtles face a real challenge in getting to the sea. In a blindly co-operative effort, the siblings get to the surface of the nest with a sporadic series of thrashings. This may take several days, and they usually emerge at night or during a rainstorm, as hot daytime sand could be lethal. Watching a clutch of turtles hatching is always a touching moment. The surface of the sands begins to twitch. A little black head appears, then a flipper, another head, and soon a gaggle of tiny clockwork toy-like hatchlings emerges.

With no adults to guide them, the newborns rely on instinct to find the sea. Strongly attracted to light, they scurry towards the dim glow reflected off the ocean’s surface. As soon as they reach the surf, the tiny turtles instinctively dive down to the bottom, riding the undertow out to calm water beyond the breakers. Then, for 24 hours or more, the hatchlings swim frenziedly to reach deeper water. Those that survive will drift the ocean currents for several years before eventually finding their way to the traditional feeding grounds on the continental shelf.

Meal in a shell

A number of different predators have learnt that breeding turtles provide an easy source of food. Crab Island, off the tip of Australia’s remote Cape York Peninsula, seems like a perfect nesting place for the rare flat-backed turtle: it is isolated and free of human disturbance — but it is also the home of massive saltwater crocodiles. These creatures, which can measure 7-8 m (23-26 feet) long, are gruesome foes, but even they find it difficult to crack open the shell of a metre-long turtle. For up to 3o minutes the crocodile thrashes the turtle in the surf. Eventually the carapace shatters and all that is left on the beach the following morning are a few scraps of shell and traces of blood.

Despite this hazard, most of the females make it safely up the beach to lay their eggs, but eight weeks later their hatchlings emerge to a different threat. Hundreds of night herons will suddenly appear and catch most of the hatch-lings as they dash for the sea. Pelicans also join in, filling their beaks with sand in their haste to steal the hatchlings before the herons. The few newborns that do make it to the water must then get past the crocodiles, sharks and fish waiting in the shallows. Given this gauntlet of predators it is hardly surprising that probably fewer than one in a thousand hatchlings survive to adulthood.

Pressure from predators may be the reason why many turtles choose to breed on islands. Although birds may pose a problem, there are likely to be fewer ground-based predators. The Olive Ridley, however, is one turtle that often nests on mainland shores. There they face a range of extra predators including ants, vultures, ghost crabs, coatis, racoons and feral pigs, but their response has been to develop a different nesting strategy,. Having discovered safety in numbers, the females return to breed in their tens of thousands for just a few nights each year. This synchronized mass nesting is called an arribada and probably plays a signifi-cant part in diluting the effect of predators.

Another mention is tiny, states that sea birds, like turtles, need solid land to reproduce:

Just like sea turtles, the world’s sea birds have no option but to return to land to breed.

Another mention is less direct, because it is about a species of seagrass that has a reference to turtles in its name (testudinum), it is eaten by turtles and often called turtle grass:

Despite this, in the afternoon, when photosynthesis and therefore oxygen production is at its peak, the leaves of Thalassia testudinum swell up 250 per cent and become oval in shape because they cannot get rid of the oxygen quickly enough.

Another mention is the mention of turtles, that among other animals, they benefit from the fact that some plants grow quickly:

Seagrass meadows also grow quickly, some plants extending by as much as 5-10 mm (0,2-0,4 in) per shoot per day, so they are a valuable source of food for herbivores, such as sea urchins, fishes, turtles and dugongs.

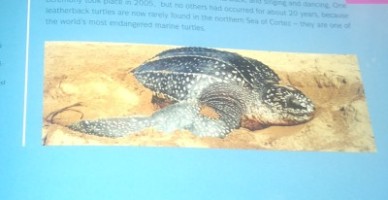

The next fragment is about leatherback turtles:

Leatherback turtles are cold-blooded reptiles which breathe air, yet still dive to depths in excess of 1300 m (4265 feet). Weighing up to 1000 kg (2200 lb), these giant creatures are superbly adapted navigators and divers, with a preferred diet of jellyfish. They migrate thousands of kilometres to reach their temperate feeding grounds, where immense concentrations of plankton are found in the deep scattering layer (> p. 328). During the night, this layer is at depths of as little as 100 m (330 feet), but by day it migrates to over 500 m (1640 feet) down.The turtles follow with ease, their bodies being coated in smooth skin to improve their hydrodynamic performance. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherbacks have a flexible shell made of ribs set in a thick, oily cartilage and covered with a pattern of bony plates. This helps them to cope with the pressures of deep diving. Most staggering of all is the speed of their dives: in as little as 10 minutes they can plummet vertically downwards for 500 m (1640 feet), feed and return to the surface, repeating the performance five times each hour.

The next piece is a caption of the photo next to the above fragment:

The massive leatherback turtle persues plankton far down in the deep scattering layer, but perhaps the most bizzare planktivore of all is the giant sunfish.

Another fragment is about bended pilot fish that like to swim with sharks and turtles:

The bended pilot fish does this, travelling in the slipstream of creatures such as sharks and turtles.

Author: XYuriTT

Title: The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design

Title: The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design