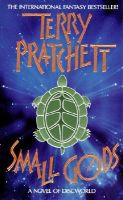

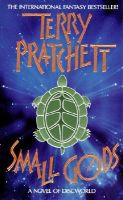

Title: Small Gods

Title: Small Gods

Author(s): Terry Pratchett

Release year: 1992

Publisher: Victor Gollancz

Why in Database: In the Discworld, this book is the most turtle – A`Tuin is only mentioned a few times here (though still, more than in some of the other entries), the main “atraction” is the god Om, who resides in the bodily form of a turtle for most of the book. A lot of interesting quotes appear, below we show many of them, but there are only a small part of all “interesting turtle things”.

At the very beginning, there is an interesting description of turtles, their perspective and relationship with eagles (this will return several times in the book):

Now consider the tortoise and the eagle.

The tortoise is a ground-living creature. It is impossible to live nearer the ground without being under it. Its horizons are a few inches away. It has about as good a turn of speed as you need to hunt down a lettuce. It has survived while the rest of evolution flowed past it by being, on the whole, no threat to anyone and too much trouble to eat.

And then there is the eagle. A creature of the air and high places, whose horizons go all the way to the edge of the world. Eyesight keen enough to spot the rustle of some small and squeaky creature half a mile away. All power, all control. Lightning death on wings. Talons and claws enough to make a meal of anything smaller than it is and at least take a hurried snack out of anything bigger.

And yet the eagle will sit for hours on the crag and survey the kingdoms of the world until it spots a distant movement and then it will focus, focus, focus on the small shell wobbling among the bushes down there on the desert. And it will leap…

And a minute later the tortoise finds the world dropping away from it. And it sees the world for the first time, no longer one inch from the ground but five hundred feet above it, and it thinks: what a great friend I have in the eagle.

And then the eagle lets go.

And almost always the tortoise plunges to its death. Everyone knows why the tortoise does this. Gravity is a habit that is hard to shake off. No one knows why the eagle does this. There’s good eating on a tortoise but, considering the effort involved, there’s much better eating on practically anything else. It’s simply the delight of eagles to torment tortoises.

But of course, what the eagle does not realize is that it is participating in a very crude form of natural selection.

One day a tortoise will learn how to fly.

One of the “factions” in the book has turtle-related “slogan”:

– “Truth is surcease from pain, Sasho. Tell me.”

“…truth…”

Vorbis sighed. And then he saw one of Sasho’s fingers curling and uncurling under the manacles. Beckoning.

“Yes?”

He leaned closer over the body.

Sasho opened his one remaining eye. “…truth…”

“Yes?”

“…The Turtle Moves…”

The first conversation between the two main characters of the book:

He picked up his hoe and turned back, in relief, to the vines.

The hoe’s blade was about to hit the ground when Brutha saw the tortoise.

It was small and basically yellow and covered with dust. Its shell was badly chipped. It had one beady eye—the other had fallen to one of the thousands of dangers that attend any slow-moving creature which lives an inch from the ground.

He looked around. The gardens were well inside the temple complex, and surrounded by high walls.

“How did you get in here, little creature?” he said. “Did you fly?”

The tortoise stared monoptically at him. Brutha felt a bit homesick. There had been plenty of tortoises in the sandy hills back home.

“I could give you some lettuce,” said Brutha. “But I don’t think tortoises are allowed in the gardens. Aren’t you vermin?”

The tortoise continued to stare. Practically nothing can stare like a tortoise.

Brutha felt obliged to do something.

“There’s grapes,” he said. “Probably it’s not sinful to give you one grape. How would you like a grape, little tortoise?”

“How would you like to be an abomination in the nethermost pit of chaos?” said the tortoise.

More details about how Om communicates:

Brutha hesitated. It dawned on him, very slowly, that demons and succubi didn’t turn up looking like small old tortoises. There wouldn’t be much point. Even Brother Nhumrod would have to agree that when it came to rampant eroticism, you could do a lot better than a one-eyed tortoise.

“I didn’t know tortoises could talk,” he said.

“They can’t,” said the tortoise. “Read my lips.”

Brutha looked closer.

“You haven’t got lips,” he said.

“No, nor proper vocal cords,” agreed the tortoise. “I’m doing it straight into your head, do you understand?”

“Gosh!”

“You do understand, don’t you?”

“No.”

The tortoise rolled its eye.

“I should have known. Well, it doesn’t matter. I don’t have to waste time on gardeners. Go and fetch the top man, right now.”

Interesting reflection on whether turtles can talk:

“Turn into a mud leech and wither in the fires of retribution!” screamed the tortoise.

“There’s no need to curse,” said Brutha.

The tortoise bounced up and down furiously.

“That wasn’t a curse! That was an order! I am the Great God Om!”

Brutha blinked.

Then he said, “No you’re not. I’ve seen the Great God Om,” he waved a hand making the shape of the holy horns, conscientiously, “and he isn’t tortoise-shaped. He comes as an eagle, or a lion, or a mighty bull. There’s a statue in the Great Temple. It’s seven cubits high. It’s got bronze on it and everything. It’s trampling infidels. You can’t trample infidels when you’re a tortoise. I mean, all you could do is give them a meaningful look. It’s got horns of real gold. Where I used to live there was a statue one cubit high in the next village and that was a bull too. So that’s how I know you’re not the Great God”—holy horns—“Om.”

The tortoise subsided.

“How many talking tortoises have you met?” it said sarcastically.

“I don’t know,” said Brutha.

“What d’you mean, you don’t know?”

“Well, they might all talk,” said Brutha conscientiously, demonstrating the very personal kind of logic that got him Extra Melons. “They just might not say anything when I’m there.

Standard for discworld books, some info about A’Tuin (non-standard is the fact, that this information is considered heresy):

Drunah broke the silence.

“De Chelonian Mobile,” he said aloud. “‘The Turtle Moves.’ What does that mean?”

“Even telling you could put your soul at risk of a thousand years in hell,” said Vorbis. His eyes had not left Fri’it, who was now staring fixedly at the wall.

“I think it is a risk we might carefully take,” said Drunah.

Vorbis shrugged. “The writer claims that the world…travels through the void on the back of four huge elephants,” he said.

Drunah’s mouth dropped open.

“On the back?” he said.

“It is claimed,” said Vorbis, still watching Fri’it.

“What do they stand on?”

“The writer says they stand on the shell of an enormous turtle,” said Vorbis.

Drunah grinned nervously.

“And what does that stand on?” he said.

“I see no point in speculating as to what it stands on,” snapped Vorbis, “since it does not exist!”

“Of course, of course,” said Drunah quickly. “It was only idle curiosity.”

Earlier, the identification slogan was mentioned, and now the drawing:

On one wall of the cave there was a drawing. It was vaguely oval, with three little extensions at the top—the middle one slightly the largest of the three—and three at the bottom, the middle one of these slightly longer and more pointed. A child’s drawing of a turtle.

Description of how turtles see people:

Besides, from a tortoise-eye viewpoint even the most handsome human is only a pair of feet, a distant pointy head, and, somewhere up there, the wrong end of a pair of nostrils.

A small sample of the common in this book “swearing” of Om’s (and also a culinary mention about the of turtles, also a recurring theme):

The tortoise bounced up and down.

“Smite you with thunderbolts!” it screamed.

“I find healthy exercise is the thing,” said Nhumrod. “And plenty of cold water.”

“Writhe on the spikes of damnation!”

Nhumrod reached down and picked up the tortoise, turning it over. Its legs waggled angrily.

“How did it get here, mmm?”

“I don’t know, Brother Nhumrod,” said Brutha dutifully.

“Your hand to wither and drop off!” screamed the voice in his head.

“There’s very good eating on one of these, you know,” said the master of novices. He saw the expression on Brutha’s face.

“Look at it like this,” he said. “Would the Great God Om”—holy horns—“ever manifest Himself in such a lowly creature as this? A bull, yes, of course, an eagle, certainly, and I think on one occasion a swan…but a tortoise?”

“Your sexual organs to sprout wings and fly away!”

“After all,” Nhumrod went on, oblivious to the secret chorus in Brutha’s head, “what kind of miracles could a tortoise do? Mmm?”

“Your ankles to be crushed in the jaws of giants!”

“Turn lettuce into gold, perhaps?” said Brother Nhumrod, in the jovial tones of those blessed with no sense of humor. “Crush ants underfoot? Ahaha.”

“Haha,” said Brutha dutifully.

“I shall take it along to the kitchen, out of your way,” said the master of novices. “They make excellent soup. And then you’ll hear no more voices, depend upon it. Fire cures all Follies, yes?”

“Soup?”

“Er…” said Brutha.

“Your intestines to be wound around a tree until you are sorry!”

Another piece, about unlucky turtles:

The Great God Om was upside down in a basket in one of the kitchens, half-buried under a bunch of herbs and some carrots.

An upturned tortoise will try to right itself firstly by sticking out its neck to its fullest extent and trying to use its head as a lever. If this doesn’t work it will wave its legs frantically, in case this will rock it upright.

An upturned tortoise is the ninth most pathetic thing in the entire multiverse.

An upturned tortoise who knows what’s going to happen to it next is, well, at least up there at number four.

A piece where Brutha reflects about the… symbolic meaning of the turtle:

He hoed the bean rows for the look of the thing. The Great God Om, although currently the small god Om, ate a lettuce leaf.

All my life, Brutha thought, I’ve known that the Great God Om—he made the holy horns sign in a fairly halfhearted way—was a…a…great big beard in the sky, or sometimes, when He comes down into the world, as a huge bull or a lion or…something big, anyway. Something you could look up to.

Somehow a tortoise isn’t the same. I’m trying hard…but it isn’t the same.

Interesting description of… “body language” in turtles:

Brutha stared at it. It looked embarrassed, insofar as that’s possible for a tortoise.

Om’s first encounter with another key (negative) character of the book:

“How very strange,” said Vorbis.

A hissing noise made him look around.

There was a small tortoise near his foot. As he glared, it tried to back away, and all the time it was staring at him and hissing like a kettle.

He picked it up and examined it carefully, turning it over and over in his hands. Then he looked around the walled garden until he found a spot in full sunshine, and put the reptile down, on its back. After a moment’s thought he took a couple of pebbles from one of the vegetable beds and wedged them under the shell so that the creature’s movement wouldn’t tip it over.

Vorbis believed that no opportunity to acquire esoteric knowledge should ever be lost, and made a mental note to come back again in a few hours to see how it was getting on, if work permitted.

Another interesting description of the turtle characteristics:

Om stumped along a sandy corridor.

He’d hung around a while after Brutha’s disappearance. Hanging around is another thing tortoises are very good at. They’re practically world champions.

A piece of human conversation about eagles, commented from the turtle’s perspective:

“Very noble bird, the eagle. Intelligent, too,” said the elderly man. “Interesting fact: eagles are the only birds to work out how to eat tortoises. You know? They pick them up, flying up very high, and drop them on to the rocks. Smashes them right open. Amazing.”

“One day,” said a dull voice from down below, “I’m going to be back on form again and you’re going to be very sorry you said that. For a very long time. I might even go so far as to make even more Time just for you to be sorry in. Or…no, I’ll make you a tortoise. See how you like it, eh? That rushing wind around y’shell, the ground getting bigger the whole time. That’d be an interesting fact!”

“That sounds dreadful,” said the woman, looking up at the eagle’s glare. “I wonder what passes through the poor little creature’s head when he’s dropped?”

“His shell, madam,” said the Great God Om, trying to squeeze himself even further under the bronze overhang.

Again, a description of… turtle behavior.

It wasn’t just the seasickness. He didn’t know where he was. And Brutha had always known where he was. Where he was, and the existence of Om, had been the only two certainties in his life.

It was something he shared with tortoises. Watch any tortoise walking, and periodically it will stop while it files away the memories of the journey so far. Not for nothing, elsewhere in the multiverse, are the little traveling devices controlled by electric thinking-engines called “turtles.”

And here is an interesting reflection about the approach to animals:

“But being cruel to animals doesn’t mean he’s a…bad person,” he ventured, the harmonics of his tone suggesting that even he didn’t believe this. It had been quite a small porpoise.

“He turned me on to my back,” said Om.

“Yes, but humans are more important than animals,” said Brutha.

“This is a point of view often expressed by humans,” said Om.

“Chapter IX, verse 16 of the book of—” Brutha began.

“Who cares what any book says?” screamed the tortoise.

Brutha was shaken.

“But you never told any of the prophets that people should be kind to animals,” he said. “I don’t remember anything about that. Not when you were…bigger. You don’t want people to be kind to animals because they’re animals, you just want people to be kind to animals because one of them might be you.”

“That’s not a bad idea!”

Fragment about the differences in the shapes of turtles:

Om wondered if tortoises could swim. Turtles could, he was pretty sure. But those buggers had the shell for it.

It would be too much to ask (even if a god had anyone to ask) that a body designed for trundling around a dry wilderness had any hydrodynamic properties other than those necessary to sink to the bottom.

More thoughts about A’Tuin:

“Om?”

“What?”

“The captain just said something odd. He said the world is flat and has an edge.”

“Yes? So what?”

“But, I mean, we know the world is a ball, because…”

The tortoise blinked.

“No, it’s not,” he said. “Who said it’s a ball?”

“You did,” said Brutha. Then he added: “According to Book One of the Septateuch, anyway.”

I’ve never thought like this before, he thought. I’d never have said “anyway.”

“Why’d the captain tell me something like that?” he said. “It’s not normal conversation.”

“I told you, I never made the world,” said Om. “Why should I make the world? It was here already. And if I did make a world, I wouldn’t make it a ball. People’d fall off. All the sea’d run off the bottom.”

“Not if you told it to stay on.”

“Hah! Will you hark at the man!”

“Besides, the sphere is a perfect shape,” said Brutha. “Because in the Book of—”

“Nothing amazing about a sphere,” said the tortoise. “Come to that, a turtle is a perfect shape.”

“A perfect shape for what?”

“Well, the perfect shape for a turtle, to start with,” said Om. “If it was shaped like a ball, it’d be bobbing to the surface the whole time.”

“But it’s a heresy to say the world is flat,” said Brutha.

“Maybe, but it’s true.”

“And it’s really on the back of a giant turtle?”

“That’s right.”

“In that case,” said Brutha triumphantly, “what does the turtle stand on?”

The tortoise gave him a blank stare.

“It doesn’t stand on anything,” it said. “It’s a turtle, for heaven’s sake. It swims. That’s what turtles are for.”

Reflection about how turtles think:

“That doesn’t sound like god talk,” he hazarded.

“It’s this tortoise brain.”

“What?”

“Don’t you know anything? Bodies aren’t just handy things for storing your mind in. Your shape affects how you think. It’s all this morphology that’s all over the place.”

“What?”

Om sighed. “If I don’t concentrate, I think like a tortoise!”

“What? You mean slowly?”

“No! Tortoises are cynics. They always expect the worst.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Because it often happens to them, I suppose.”

A reference to another book by Pratchett, Pyramids, where philosophers very literally searching/testing for turtles faster that arrows:

“Evening, sir,” he said. “What’ll it be?”

“I’d like a drink of water, please,” said Brutha, very deliberately.

“And something for the tortoise?”

“Wine!” said the voice of Om.

“I don’t know,” said Brutha. “What do tortoises usually drink?”

“The ones we have in here normally have a drop of milk with some bread in it,” said the barman.

“You get a lot of tortoises?” said Brutha loudly, trying to drown out Om’s outraged screams.

“Oh, a very useful philosophical animal, your average tortoise. Outrunning metaphorical arrows, beating hares in races…very handy.”

Explanation of the genesis of the slogan used by “conspirators”:

“The Turtle Moves,” said Urn thoughtfully.

“What?” said Brutha.

“Master did a book,” said Urn.

“Not really a book,” said Didactylos modestly. “More a scroll. Just a little thing I knocked off.”

“Saying that the world is flat and goes through space on the back of a giant turtle?” said Brutha.

“Have you read it?” Didactylos’s gaze was unmoving. “Are you a slave?

Some joke(s) about the turtle(s):

Then he said, “You aren’t going to say they’re a relic of an outmoded belief system?”

Didactylos, still running his fingers over Om’s shell, shook his head.

“Nope. I like my thunderstorms a long way off.”

“Oh. Could you stop turning him over and over? He’s just told me he doesn’t like it.”

“You can tell how old they are by cutting them in half and counting the rings,” said Didactylos.

“Um. He hasn’t got much of a sense of humor, either.”

Another fragment about the nature of the discworld /A’Tuin:

“And this is the book Didactylos wrote,” said Urn.

Brutha looked down at a picture of a turtle. There were…elephants, they’re elephants, his memory supplied, from the fresh memories of the bestiary sinking indelibly into his mind…elephants on its back, and on them something with mountains and a waterfall of an ocean around its edge…

“How can this be?” said Brutha. “A world on the back of a tortoise? Why does everyone tell me this? This can’t be true!”

“Tell that to the mariners,” said Didactylos. “Everyone who’s ever sailed the Rim Ocean knows it. Why deny the obvious?”

“But surely the world is a perfect sphere, spinning about the sphere of the sun, just as the Septateuch tells us,” said Brutha. “That seems so…logical. That’s how things ought to be.”

“Ought?” said Didactylos. “Well, I don’t know about ought. That’s not a philosophical word.”

“And…what is this…” Brutha murmured, pointing to a circle under the drawing of the turtle.

“That’s a plan view,” said Urn.

“Map of the world,” said Didactylos.

A very important life wisdom:

“Getting plenty of sleep is vital,” said Om. “It builds a healthy shell.”

Nice fragment about turtles:

“Oh, I know you exist,” said Brutha. He felt Om relax a little. “There’s something about tortoises. Tortoises I can believe in. They seem to have a lot of existence in one place. It’s gods in general I’m having difficulty with.”

Another description-interpretation of turtle behavior:

Om’s head darted into his shell for a moment, the nearest he was capable of to a shrug.

More about A’Tuin:

You can’t believe in Great A’Tuin,” he said. “Great A’Tuin exists. There’s no point in believing in things that exist.”

“Someone’s put up their hand,” said Urn.

“Yes?”

“Sir, surely only things that exist are worth believing in?” said the enquirer, who was wearing a uniform of a sergeant of the Holy Guard.

“If they exist, you don’t have to believe in them,” said Didactylos. “They just are.” He sighed. “What can I tell you? What do you want to hear? I just wrote down what people know. Mountains rise and fall, and under them the Turtle swims onward. Men live and die, and the Turtle Moves. Empires grow and crumble, and the Turtle Moves. Gods come and go, and still the Turtle Moves. The Turtle Moves.”

From the darkness came a voice, “And that is really true?”

Didactylos shrugged. “The Turtle exists. The world is a flat disc. The sun turns around it once every day, dragging its light behind it. And this will go on happening, whether you believe it is true or not. It is real. I don’t know about truth. Truth is a lot more complicated than that. I don’t think the Turtle gives a bugger whether it’s true or not, to tell you the truth.”

Another interesting reflection on how turtles perceive the world:

He crawled through the bushes, their thorns scraping harmlessly along his shell. He passed another tortoise, which wasn’t inhabited by a god and gave him that vague stare that tortoises employ when they’re deciding whether something is there to be eaten or made love to, which are the only things on a normal tortoise mind. He avoided it, and found a couple of leaves it had missed.

Again about turtle behavior:

Om fought to stop his head and legs retracting automatically into his shell, a tortoise’s instinctive panic reaction.

Turtle, exceptionally, in a different meaning than previously spoted, i.e. a defensive/combat formation:

“Do you know what a tortoise is?”

Urn scratched his head. “Okay. The answer isn’t a little reptile in a shell, is it? Because you know I know that.”

“I mean a shield tortoise. When you’re attacking a fortress or a wall, and the enemy is dropping everything he’s got on you, every man holds his shield overhead so that it…kind of…slots into all the shields around it. Can take a lot of weight.”

“Overlapping,” murmured Urn.

“Like scales,” said Simony.

Urn looked reflectively at the cart.

“A tortoise,” he said.

Again, a nice quote:

No one saw the tiny speck, tumbling down from the sky.

Don’t put your faith in gods. But you can believe in turtles.

The last turtle fragment that we quote:

“I know him—” said Borvorius. “Vorbis! Someone killed him at last, eh? And will you stop trying to sell me fish? Does anyone know who this man is?” he added, indicating Fasta Benj.

“It was a tortoise,” said Brutha.

“Was it? Not surprised. Never did trust them, always creeping around.

Author: XYuriTT

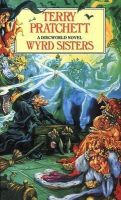

Title: Wyrd Sisters

Title: Wyrd Sisters