Title: Blue Planet II

Title: Blue Planet II

Author(s): James Honeyborne, Mark Brownlow

Release year: 2017

Publisher: BBC Books

Why in Database: A book supplement to the nature series with the same name, with many many turtle elements! We found as many as 12 pictures and many fragments in the text. We quote them all below:

The Arrival

During the course of the day, dark, round shadows appear in the shallow inshore waters off beaches on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. They are not inanimate rocks but living Olive Ridley sea turtles, and for several hours they sit motionless on the seabed, resting, maybe even asleep, conserving nergy prior to a coming event that will require a herculean effort.

By early evening, they begin to stir. They swim parallel to the shore, their small heads bobbing above the surface to catch a breath, before submerging for five minutes or so at a time as if preparing for the big moment. Then, at some unknown signal, they start to emerge from the sea. changing from animals that are totally at home in the water to animals that are very uncomfortable on land.

At first, there are just twenty or thirty hauling their heavy bodies out of the surf, but gradually numbers increase until the beach resembles a moving conveyor belt of round, grey boulders. Many thousands of turtles will be crossing the beach and throughout the night they will just keep coming because they have to. Sea turtles are an ancient group of reptiles that are still bound to the land for this one vital purpose-to lay their eggs- so mothers must cross the frontier between land and sea and, for several exhausting hours, leave the confines of the ocean. It’s a huge challenge, but despite the hardships, the rewards are worth it.

It is the rainy season on a dark night a few days before the three-quarter moon, and these female sea turtles have come to deposit their eggs in the black volcanic sand. It is known locally as the arribada (“arrival”), and it is rely one of the most traumatic thing female sea turtle has to do during her life. More used to being supported by the water, her heavy body pushes down painfully on her internal organs, including her lungs. She wheezes and coughs, and glutinous tears ooze down from the corners of her eyes.

She sniffs at the sand, and when it is the right consistency and dampness she starts to dig. Using her spade-like hind limbs, she excavates a pit the shape of a teardrop. Manoeuvring her bulk over the hollow, she lets out a huge sigh, and slowly and deliberately she deposits up to 100 eggs, each the size of a ping-pong ball. Then, using her front flippers, she covers them and, with one last gargantuan effort, hauls her body back to the sea.

If she was the only turtle on the beach, her clutch would be undisturbed and probably many of her embryos would develop successfully and later hatch out, but she is not alone. Thousands of other mothers are excavating the same stretch of sand, the late arrivals inadvertently digging up the eggs of the early birds. It is just what the egg thieves have been waiting for.

Black vultures, wood storks and great-tailed grackles are in the vanguard, and this is their moment. They squabble for the exposed nests, some even snatching the soft-shelled eggs at the very moment they are laid. Coatis, recognised by their erect, striped tails and long snouts, dig up buried eggs, Stray dogs and feral pigs join them, rooting around in the sand, yet there is plenty for all. During the course of a single arribada over several days, hundreds of thousands of females emerge from the sea, and they deposit tens of millions of eggs safely beyond the reach of the tide. With so many eggs, predator swamping’ means that the thieves cannot eat them all, and nesting at night reduces the risk of nest predation. Some babies will have a chance to grow.

When the mothers go back to the sea, they all head off their separate ways. Olive Ridley sea turtles are more at home in the open ocean alone than on the shore with thousands of others of their own kind, but before they hit deep water they must run a gauntlet of sharks and American crocodiles from a nearby estuary. Even if they get past and survive, the fishing nets are another danger. In the past, thousands of turtles were caught in fine-meshed shrimp nets dragged by trawlers; many were drowned, and the population dwindled. Now local fishermen must by law have nets with turtle-excluder devices that enable the turtles to escape. It means a few more will return to join the next arribada.

THE WAIT (opposite) Olive Ridley sea turtles are a solitary, open-ocean species. During the day, they wait just offshore, as if preparing for the transition from water to land.

ARRIBADA (below and overleaf) Thousands of female Olive Ridley sea turtles emerge from the ocean to deposit their eggs in the sand of a Costa Rican beach.

BEACH TRAVELLATOR (opposite) Latecomers arrive just as the early birds leave, the former often digging up the eggs of the latter.

MOB RULE (below) Despite the superabundance of turtle eggs, two black vultures still fight over possession. They steal eggs even before the mother turtle has had time to finish depositing and burying her clutch.

The Olive Ridley sea turtles are short-term visitors to the coast, but at Roebuck Bay on the west side of the Dampier Peninsula in Western Australia there are animals that take advantage of high tides over vast mud flats, rich in food.

While the fish and shrimps are exchanging audible brickbats, the local sea turtles are just waking up and getting ready to do battle.

Turtle Rock Health Spa

In any great city, the morning rush hour sees commuters racing to their destinations, and the coral reef metropolis is no exception. Time wasted is feeding time lost, but for some the first appointment of the day is a visit to the health spa.

An old female green sea turtle emerges from the coral overhang under which she has spent most of the night asleep, lodged firmly in place to prevent her from floating up to the surface between breaths. While inactive she can hold her breath for several hours, but now it is time to move, and move fast. She wants to be first at the spa, and for the moment there’s not another turtle in sight.

A sea turtle with algae covering its carapace and parasites on the softer parts of its body is going to be slower, less healthy and at a disadvantage compared to one without, so she heads for the wash-and-brush-up service provided by local cleaner fish. It would have been better to saunter. The disturbance has other turtles, and they’ve noticed she’s making a break for it. There is only room for one turtle at a time at the spa, so the race is on.

On the reef at Sipadan, off the coast of Malaysian Borneo, Turtle Rock is a world-famous cleaning station. It is an unusual undersea landmark because the rocky outcrop has a well-worn hollow in the top that has been eroded by countless generations of sea turtles checking in to be cleaned. The first to arrive receives the five-star treatment, so the queue can involve a bit of argy-bargy, as underwater cameraman Roger Munns found out:

‘Green turtles have a well-deserved reputation for being very docile, but they are not so friendly when they want their shells cleaned at Turtle Rock. They bite and headbutt each other in order to get the best spot. They’re very aggressive.”

When the other turtles catch up and crowd in, they bite the lead female’s flippers and generally make life difficult for her, but it’s all to no avail: the first in is the first to be spruced up. Bicolour blennies appear from their burrows in the coral, and dark surgeonfish hover expectantly, ready to service the first customer of the day. The blennies deal with the parasites and dead skin, while the surgeonfish nibble on the algae covering the turtle’s shell. With this arrangement, the fish get an easy meal and the turtle a smoother shell and clean skin, the symbiotic relationship between them known as ‘mutualism’, meaning both parties benefit. It’s another way for them both to gain an advantage in the city.

LATE ARRIVALS (above) On one occasion, the film crew had to wait for over four hours for the turtles to turn up and settle into the cleaning station, and all for a 20-second shot!

TURTLE ROCK (opposite) Normally docile green sea turtles become very aggressive towards competitors for acces to this often used cleaning station

In fact, scientists now think that some of the larger animals feeding on the seagrass, such as green sea turtles and dugongs, actually obtain much of their nutrients, not from the seagrass leaves themselves, but from the ‘micro-forest’ of epiphytic algae.

Seed-Spreading Turtles

Green sea turtles are carnivorous for the first part of their lives. As juveniles they feed on sponges, jellyfish, fish eggs, molluscs, worms, and crustaceans, but when they reach adulthood, they switch to a predominantly herbivorous diet, chomping on seagrass and algae, and that’s not all. Aside from regularly trimming the seagrass meadow, they appear to have an important role in spreading it. It was once thought that only ocean currents dispersed seagrass seeds, but evidence is accumulating that turtles, and some of the other seagrass consumers, are at least partly responsible. The average green turtle eats about 2 kilograms of leaves and defecates about 25 seeds a day, and turtles tend to return to areas where seagrass traditionally grows, so they reseed old grounds as well as starting new ones.

Furthermore, in the laboratory, seeds germinate faster after having passed through the turtle’s gut. Seagrasses evolved about 100 million years ago and turtles have been eating seagrass for close to 50 million years, so it is possible the two species have co-evolved.

There is always the danger, of course, that an overly large population of turtles would strip out all of the seagrass, whether they replant it or not, but nature has an answer for that too. Tiger sharks protect the seedlings by keeping turtles in check!

UNDERWATER MOWER (above) An adult green sea turtle chomps on seagrass. It bites off the tips of the blades of grass with its serrated jaw, which, like a well-mown lawn, keeps the meadow healthy.

The shark patrol the lush parts of the seagrass meadows because that is where they expect the turtles and dugongs to be feeding, but the prey is smarter than that.

One was filled with 28,800 bathroom toys – plastic yellow ducks, green frogs, blue turtles and red beavers – but it burst apart, spilling its contents into the sea.

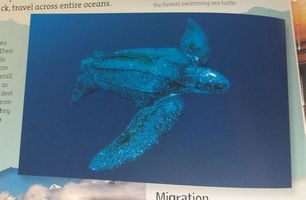

In the Pacific, a jellyfish-eating leatherback sea turtle embarked on the longest turtle migration ever recorded. It travelled 20,558 kilometres from its nesting beach on Papua in the southwest Pacific to jellyfish-rich feeding areas off the coast of Oregon in the northeast Pacific, and was on its way back when its tracking signal was lost. Like all marine reptiles, they must surface to breathe and so a turtle’s head popping out of the water might well be the source of many ‘sea serpent’ sightings in northern waters.

Lost Years and a Log

The fallen bough, washed into the sea by a river or toppled from coastal cliffs, becomes encrusted with barnacles and algae, and young sea turtles come to feed on them. The log is their temporary life raft, and their presence here has solved a long-standing biological mystery. When turtle hatchlings leave their beach, they head out into the open ocean and are probably faced with the most challenging times of their life, what scientists have dubbed the ‘lost years’ because nobody knew where they went until they returned to lay eggs five years later. Now we know.

‘We stumbled on the answer without fully realising it, John Ruthven reveals. ‘More than 160 kilometres off the coast of eastern Australia, with 3 kilometres of clear water below, we spotted a floating log. Diving below it, we found many creatures hiding, including a young hawksbill sea turtle not little, not large, but middle-sized. This is probably where it spends its so-called ‘lost years’.

‘Scientists can trace the paths of small turtles like this using miniature satellite tags. They show that hatchling turtles go far out to sea, and temperature sensors on the tags reveal that the little reptiles keep warm and develop faster by staying close to the surface, sheltered by floating objects.

‘After hatching, a baby turtle faces a daunting gauntlet of predators near the coast, and so it takes its chances on the high sea. When some inquisitive oceanic whitetip sharks came by, I wondered if this wasn’t much of a choice, but anything a turtle can do to improve its one-in-a-thousand odds of reaching adulthood must be useful,’

The young sea turtles ride the ocean currents, like many young marine creatures, hiding beneath flotsam, jetsam, logs and rafts of floating seaweeds, such as those found in the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic Gyre. Here, drift lines of Sargassum, a type of brown seaweed kept afloat by airbladders, are host to their own specialist community of animals, like the sargassum crab and the exquisitely camouflaged sargassum fish. These are the preferred hiding places for young turtles, but these miniature hotspots also attract unwelcome guests, and the predators of the open ocean are amongst the most inquisitive, none more so than the oceanic whitetip shark, which John had seen prowling.

At the slightest hint of food, the oceanic whitetip swims in directly and without fear. It may not have fed for weeks, so it wastes no time. It prefers fish to turtles, so an attack would be an exception, but there is another large and dangerous species with chainsaw-like teeth that would make easy work of a young sea turtle’s shell, and it deliberately targets these ocean drifters. It’s the tiger shark, thought until recently to be mainly a coastal species. However, tagging studies have shown that tiger sharks from the Caribbean head out a short distance into the Atlantic each summer in search of young, naïve and easy-to-catch loggerhead turtles.

OCEAN HIDING PLACE (below) A young sea turtle finds refuge amongst a floating mat of sargassum.

Garbage Patch Ocean

At one time, the debris in which young sea turtles hide was mainly natural, but nowadays a flood of plastics dominates. It is thought that the equivalent of a large garbage-truck-load of plastic is dumped into the sea every minute of every day. The effects are an ecological nightmare.

Thousands of sea turtles are either strangled by discarded nylon fishing gear or choke on plastic bags, mistaking them for jellyfish. It is estimated that over half of living turtles have eaten plastic at some time in their life, and about 90 per cent of seabirds have consumed plastic particles that they have mistaken for food.

PLASTIC JELLYFISH (opposite top) A green sea turtle mistakes a clear plastic bag for a jellyfish off the coast of Tenerife.

Lo and behold, the fossil skeletons of plesiosaurs and ancient sea turtles that lived about 100 million years ago have been found with the tell-tale excavations of zombie worms.

Plastic bags and the larger pieces of plastic block the intestines of whales, sea turtles and birds, such as albarosses, or kill chicks because their parents have fed them plastics.

Author: XYuriTT

Title: Incedible Journeys Amazing Animal Migrations

Title: Incedible Journeys Amazing Animal Migrations

Title: Frozen Planet II

Title: Frozen Planet II

Title: India Nature’s Wonderland

Title: India Nature’s Wonderland

Title: Earth’s Tropical Islands

Title: Earth’s Tropical Islands