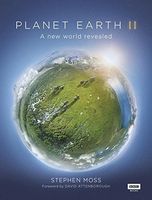

Title: Planet Earth II: A New World Revealed

Title: Planet Earth II: A New World Revealed

Author(s): Stephen Moss

Release year: 2016

Publisher: BBC Books

Why in Database: A supplementary book for the nature series Planet Earth II. There are several turtle fragments and two full-page photos.

The first turtle reference is in a foreword by David Attenborough:

It was a blissful time for those of us making natural history programmes. Even in Africa, where many of the animals were so familiar, we could easily find creatures that were quite new to most viewers – porcupines, chameleons and turtles. And if we went to other continents there were all kinds of astonishments – wombats and narwhals, hummingbirds and armadillos, manatees and sloths.

The jaguar is an excellent swimmer and, like most big cats, an opportunist, hunting a wide range of prey, from freshwater turtles and armadilos, to capybaras and deer.

In the absence of of their old predators or competitors, many animals (and plants) have developed unusual characteristics. Some are bigger than their mainland cousins – the Galapagos tortoises, for example.

The biggest tortoise

Small may not always be the best route to survival on an island, and many creatures display the opposite trait: they become giants. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the Galápagos Islands. Off the Pacific coast of South America, straddling the equator, the Galápagos gained their worldwide fame as the cradle of evolutionary theory when Charles Darwin visited in the 1830s. Observing the strange life forms he encountered, adapted to different situations, led him to develop his theory of evolution through natural selection.

Of all the creatures he came across, few were as impressive as the giant tortoises. They weigh on average roughly the same as three grown men. Once, these huge reptiles roamed across many of the world’s continents, but today they are only found on two island groups, separated by thousands of miles of sea: Aldabra in the Indian Ocean, and the Galápagos, where they live on 7 of the 21 islands. These reptiles are not only huge but also among the longest lived of any animal surviving more than a century in the wild (up to 170 years in captivity). Of the 13 known races, 11 survive today.

Like many of the other creatures on the Galápagos, the giant tortoises were castaways, drifting across the ocean from mainland South America. They managed to travel such a distance – some 1000km (620 miles) – because they float and can survive for several months without food or water. Helped by ocean currents, though some would have drifted westwards, enough made landfall for a viable population to become established.

Darwin was stunned by the size of these reptiles, noting in his journal that it took up to eight men to lift a tortoise. So why are they so big? One theory suggests that only the largest tortoises could have survived such a difficult sea crossing, as their large volume to surface area ratio would have allowed them to retain fluids, while their longer necks meant they could breathe more easily.

The other notable feature is how the shape of their shells differs. The shapes seem to correlate with the habitat of the island on which they live: those on lush, well-vegetated islands have domed shells and shorter necks; those on dry, desert-like islands have ‘saddleback’ shells and long necks. Presumably, where there is plenty of low-growing vegetation, the animals can easily reach their food, while on drier islands, they may need to reach up to get to taller vegetation such as the abundant prickly pear cactus. However, other scientists have suggested that this may be a coincidence and that the saddleback shell shape is actually a product of sexual selection, a result of generations of females preferring males with a higher front to their shell and longer necks. But then two races that have a similar shape may not necessarily be very closely related, which tends to suggest that they have evolved in response to the type of habitat in which they live.

Famously, at the time of his visit, Darwin falled to appreciate the differences in shell-shape between each island tortoises. Only when he returned to England did he develop his theory; and then, to his eternal regret, he found that he had not always labelled the tortoise shells he had collected with the name of the island where it had been found – thus making the specimens far less useful for determining whether his assumptions were correct.

When the islands were discovered in the sixteenth century there were as many as a quarter of a million giant tortoises; today there are just a few thousand. But with better habitat conservation, and the removal of introduced animals, their future now looks more assured.

The text below is a description of the picture of the Aldabra tortoise, which is shown next to the long text quoted above:

The biggest survivor. Aldabra giant tortoise, on the remote Indian Ocean atoll of Aldabra – part of the Seychelles group. It is more than a metre long (more than 3 feet), and is the only species of giant tortoise to have survived in this part of the world, the others having been hunted to extinction by visiting seafarers or settlers or their habitat destroyed by introduced animals accompanying humans. These giants can live for more than 100 years, probably more than 150.

So long as the niche you fill is unocuppied, it makes sound evolutionary sense to be either tiny or, if you are a tortoise on the Galapagos or Aldabra, very large indeed.

Turtles have been coming to Barbados to lay their eggs for thousands of years, but now light from the holiday resorts is throwing the hatchlings off track. On emerging, they need to head to the water as fast as they can to avoid being picked off by predators such as gulls. They have evolved to head to the brightest horizon – the water reflecting the light of the moon. But today the brightest glow comes from the hotels and restaurants, which takes the hatchlings in exactly the wrong direction. Red crabs then gather under the streetlights, picking them off before they ever reach the sea. For these turtles, which have seen urbanization take over their once-pristine natural nurseries, the future would be bleak were it not for the conservationists who are helping the hatchlings make it to the sea.

The caption for the second turtle photo in the book, with a leatherback turtle, placed next to the text above:

Lure of the nightlight. On Juno Beach, Florida, a leatherback sea turtle hauls up to lay her eggs. When the baby turtles hatch, they head for the brightest horizon, which should be the natural glow of moon on the sea. But light from beachfront development can lead them off course, and wandering hatchlings can be hit by cars or caught by predators.

On the Caribbean island of Barbados (as on the beaches elsewhere), hatchling turtles are so confused by the lights of beach developments that they head away from the sea rather than towards it, and the shoots at night mostly recorded baby turtles dying in street gutters.

Author: XYuriTT