Title: Last Chance to See: In the Footsteps of Douglas Adams

Title: Last Chance to See: In the Footsteps of Douglas Adams

Author(s): Mark Carwardine

Release year: 2009

Publisher: HarperCollins

Why in Database: A book directly referring to the Last Chance to See book, published less than 20 years earlier. In this book Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine traveled the world and watched very rare species, on the verge of extinction in first book. In 2009, one of this pair, Mark, with Stephen Fry as companion decided to recreeate the traces of that expedition. We also have TV version of this book/joruney described. This position is much more turtle than the original, e.g. the heroes visit the turtle hatcheries .

The first, four-page fragment, which we cite in full, as about mentioned above turtle hatchery, where scientists and volunteers make sure that the eggs of sea turtles can develop safely and safely. All four photos we added below the quotes are from this fragment.

Something I really must tell you about, before it’s too late, is one of the greatest evenings of Stephen’s life. I know that’s true because he actually said ‘That was one of the greatest evenings of my life.’

It was one of mine, too.

We were still off the north coast of Borneo, this time on Selingan Island, in Turtle Island National Park. And we had 24 hours to spend quality time with a heavily protected population of endangered green sea turtles.

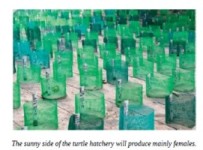

There is a turtle hatchery on the island and we were shown around by Nicholas Pilcher – a fellow Brit as well as a world-renowned turtle expert. The hatchery consisted of hundreds of artificial turtle nests in neat rows across the sand next to the park headquarters. Each nest was labelled, with a date and the number of eggs inside, and protected with a circle of plastic mesh roughly the size of a bucket.

One of the many threats facing sea turtles around the world is eggcollecting (the eggs are taken from the nests and eaten), so transferring the eggs to properly guarded hatcheries is a good way of keeping them safe.

We actually collected some from a female who had dug a nest under the mangroves at the back of the beach. I had the enviable job of leaning right into the depression behind her and scooping up her clutch as the eggs came out. She laid 95 altogether. They were warm and roughly the size and shape of table-tennis balls, though much heavier and softer.

We carried them back to the park headquarters, where they were placed inside one of the artificial nests.

‘It’s another example of how conservationists have to do almost exactly the same as poachers,’ observed Stephen. ‘Here we are collecting eggs – just like poachers. The difference, of course, is that we’re doing it to help save the species.’

We took a closer look at some of the nests already under protection. We paused at one of them and looked at the marker post: 81 eggs buried on 13 January 2009. It was 24 March 2009 – exactly seventy days later. Suddenly, a tiny hatchling appeared out of the sand. Then there was another, and another. Just as we realised what was happening, the entire nest erupted and they all scrabbled out like bubbling lava. I leant in towards the nest and it sounded like a pot of boiling water.

Nick was delighted.

‘On the day of hatching,’ he said, ‘they make their way up towards the outside world and wait patiently in a queue just beneath the surface of the sand. As soon as the light starts to fade, as it is now, they begin to emerge.’

Nick went to get a basket and, very gently, we lifted the tiny, perfectly formed turtles out, one by one. Their shells were soft and leathery, and they felt incredibly delicate.

‘It’ll be a while before they harden,’ Nick told us.

‘Ooh!’ said Stephen. ‘Aah! My darling!’

(The last time I’d heard him talk like that was when we released the adorable little Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur in Madagascar.)

Sixty-three hatchlings made it out altogether. It was a heart-wrenching moment, because we knew that very few of them would survive. The life expectancy of turtle hatchlings is worse than for drug-taking members of street gangs in Los Angeles – as few as one in a hundred survive long enough to become mature breeding adults.

‘Can you tell if these are male or female?’ asked Stephen.

‘Not just by looking at them,’ answered Nick, smiling. ‘But my guess is that they will be female. Have you noticed that the hatchery is half in the shade and half in the sun?’

Stephen looked up at the green fabric roof above our heads and nodded.

‘Well, that’s intentional – so that half the nests are slightly warmer, by a couple of degrees, than the other half. The warmer nests will produce mainly females and the colder ones mainly males. It enables us to manage the population more carefully.’

We carried the basket of scrabbling turtle hatchlings down to the beach.

‘We’ll release them here,’ said Nick. ‘We need to give them a run-up before they enter the sea. That gives them a chance to get their bearings, to set their internal magnetic compasses, so they are able to navigate when they get out to sea.’

‘Where will they go?’ I asked.

‘Nobody knows for sure. The next few years of their lives have been dubbed “the lost years” because they are hardly ever seen. They probably get swept along at the mercy of the ocean currents. How they eventually get their bearings and swim back to the place they were born is a complete mystery.’

We watched in awe as the hatchlings made their perilous dash for the sea.

‘Notice how they’re all heading straight towards the setting sun,’ said Nick. ‘They always head for the brightest point in the sky. It’s a big problem when they emerge from nests on tourist beaches, of course, because they head for the hotel lights instead.’

‘Oh my God!’ shouted Stephen suddenly. ‘One’s been grabbed.’

We rushed over to see a hatchling disappear down a hole in the sand. I rescued it just in time and let it go a safe distance away. I know you’re not supposed to intervene in nature, but I’m afraid I couldn’t resist. Our hatchlings needed all the help they could get. Plus they were irresistibly cute.

‘That was a ghost crab,’ said Nick. ‘Lots of hatchlings get picked off on their way to the sea, not just by crabs but by gulls and rats and things.’

The hatchlings ran straight into the surf without skipping a beat, diving into the waves and swimming as if they’d been doing it their whole lives.

‘Unbelievable,’ I said to Stephen. ‘I just can’t believe this is the first time they’ve ever set eyes on the sea – and yet, there they go, as if it’s the most natural thing in the world.’

‘I suppose it is the most natural thing in the world,’ he replied.

Without the benefit of swimming lessons, the baby turtles started swimming automatically. Their flippers did an intriguing mix of doggy paddle and breaststroke, while their heads bobbed up and down so they could breathe. They looked just like clockwork toys.

‘I wonder how many of them will make it?’ asked Stephen.

‘I’m afraid the odds are not very good,’ answered Nick. ‘They’ve survived the hazards of the beach…’

‘With our help,’ I interrupted.

‘Yes, with our help,’ smiled Nick. ‘But now they have to run the gauntlet of the reef, where there are loads of hungry fish that would love to snack on them. They’ll just keep swimming frantically for a day or two until they are far out in the open sea, where they might be able to hide in floating seaweed and be a little safer.’

The hatchlings will be looking over their shoulders for about a year, by which time they will be roughly the size of saucers and their shells will have hardened enough to make them less easy prey for predators.

But even as adults they face a barrage of threats. One of the biggest dangers comes in the form of fishing nets – tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of sea turtles die in them every year.

We watched as the last of the hatchlings disappeared beneath the waves.

‘Hopefully,’ said Nick, ‘one of them will be back, in maybe 20 or 25 years’ time, to lay her eggs on the same beach, right here, where she was born.’

‘Good luck,’ called Stephen to the now-invisible babies. ‘I’ve never seen anything quite so magical in my entire life.’

Another fragments tells about what the heroes saw underwater during diving – many green turtles and a few smaller hawksbill turtles:

The turtles were another star attraction. They were everywhere. Most of them were massive green turtles, but there were a few smaller hawksbills too. We must have seen at least a dozen altogether.

When the author directly quotes Stephene Fry, about what he saw underwater, he mentions turtles and sharks.

Amazing. And all those things I can’t identify? They are amazing, too. Not to mention all the turtles and sharks. But I have to say I really like the small stuff – I could have stayed in just one place for an hour and not got bored.’

Another turtle fragments are author’s recollection, which tells that he has been exploring the Baja region since the late 1980s, he dived with sharks, swam with turtles, etc.:

I’ve been exploring Baja since the late 1980s, diving with sharks, snorkelling with turtles, surveying blue whales from the air, photographing lots of other whales and dolphins from boats, and much, much more.

Kolejny fragment dotyczy rysunków naskalnych jakie bohaterowie widzieli w Mexicou, w tym żółwia morskiego.

Behind us was a huge rocky overhang, which was literally covered in cave paintings. We recognised several different animals: lots of antelopes, a fish (or maybe it was a whale?), some rabbits, a couple of birds and a sea turtle. There were human figures, too, though they looked unlike any people we knew. Some were wearing what looked like top hats, others appeared to be in their pyjamas, and several looked more humanoid than human. One, clearly a woman, had eye-catchingly long breasts that dangled down to her knees.

Another turtle is mentioned in reference to a pilot who is flying “over everything”, from pronghorn and geese to turtles and whales (of course, it is about flying “to observe from the air”):

Sandy Lanham is a pilot – one of the best I’ve ever flown with – who runs a non-profit organisation that conducts aerial surveys for underfunded conservationists and researchers in Mexico and the United States. She flies over everything from pronghorn antelopes and geese to sea turtles and whales.

In the next fragment, the author fears whether any conclusions will be drawn from the fate of Baiji (a type of dolphin living in the Yangtze), because there are also other species in this river that may soon disappear, including “Asian softshell turtle”:

Will we learn any lessons from the loss of the baiji? It’s an important question, because there are other endangered species in the Yangtze River that could disappear soon, including everything from the Asian softshell turtle to the smooth-coated otter. In other parts of the world, we should be worrying about two of the baiji’s closest relatives, the Indus and Ganges river dolphins, which face remarkably similar threats and are disappearing fast. And, of course, there is all the other, unrelated wildlife struggling for survival in all corners of the globe.

The last mention is made at the end of the book, where the author wonders if there is any chance for endangered species:

I’ll never forget meeting Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur in Madagascar, tickling a thirty-tonne grey whale under the chin in Mexico, releasing a bucketful of turtle hatchlings in Borneo, or learning to love chimps in Uganda. Not to mention being ravished by a man-eating kakapo in New Zealand.

But there’s one thing I can’t get out of my mind. Twenty years have passed since my original travels with Douglas Adams – twenty years of rigorous and intensive conservation work, by countless people from all walks of life, costing untold millions of pounds. Yet for all these efforts, the natural world is not really a better place.

Yes, there have been some outstanding success stories and, of course, it’s not all doom and gloom. But my overriding impression – and that of a great many of the people we met working in the field – is that we are slowly, but surely, losing the battle. Don’t get me wrong – I haven’t given up hope. The number of people who have devoted their lives to protecting the likes of gorillas, robins, turtles and lemurs is sufficient cause for optimism. Besides, we must be doing something right, if only because a large number of endangered species haven’t (yet) become extinct.

Author: XYuriTT