Tytuł: Żyjąca Planeta

Tytuł: Żyjąca Planeta

Tytuł oryginału: The Living Planet

Autor(zy): David Attenborough

Tłumaczenie: Ewa Pankiewicz

Rok wydania: 1984 (ENG), 1997 (PL)

Wydawnictwo: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd.

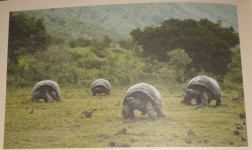

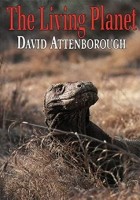

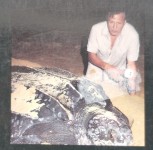

Dlaczego w bazie: Baaardzo żółwia pozycja, przytaczamy siedem fragmentów, z czego dwa są dosyć potężne. Ponadto pokazujemy trzy żółwie zdjęcia jakie w środku można znaleźć a także zdjęcie autora, Davida Attenborough z żółwiem skórzastym. Wersja mała pochodzi z wydania w miękkiej okładce, wersja duża zaś z obwoluty wydania w twardej okładce. Mamy w bazie także telewizyjną serię przyrodniczą o takim samym tytule, której książka jest częścia.

W normalnych okolicznościach częste i szybko przemieszczające się pożary nie sprawiają zwierzętom specjalnego kłopotu. Ptaki mogą odlecieć. Zwierzęta żyjące na ziemi, takie jak grzechotniki i żółwie norowe, na kilka minut trwania pożaru chronią się w norach, w których zazwyczaj chowają się w południe przed trudnym do zniesienia upałem.1

Żółwie, gdy ogrzeją się naprawdę mocno – powyżej czterdziestu i pół stopnia Celsjusza – wydzielają dużo śliny, którą zwilżają głowę i szyję. Cz. ii posuwają się nawet dalej i obficie uwalniają płyn nagromadzony w pęcherzach analnych uchodzących do kloaki.2

Ryby żyjące w rzekach atakowane są także przez innych myśliwych. Czychają na nie żółwie leżące na dnie. Nie są one szybkimi pływakami, lecz łapią ryby wykorzystując element zaskoczenia. Matamata – żółw z południowej maskuje się za pomocą frędzli skórnych, zwisających z fałd na głowie i pod, pancerz również jest nierówny, a często jeszcze porośnięty „kożuchem” z glonów. Zwierzę, które zgodnie ze swym zwyczajem leży na dnie pomiędzy gnijącymi liśćmi, staje się praktycznie niewidoczne. Gdy w jego zasięgu zabłąka się jakaś ryba, żółw nagle rozdziawia paszczę i pochłania ofiarę.

Żółw sępi, jeden z największych żółwi słodkowodnych, który dochodzi do siedemdziesięciu pięciu centymetrów długości, wykazuje większą aktywność w łowieniu ryb. Na jego języku znajduje się długi wyrostek robakowatego kształtu, który służy do wabienia ryb. Żółw sępi spoczywa na dnie z rozwartymi szczękami i co jakiś czas wprawia w ruch swą małą czerwoną przynętę. Gdy zjawi się ryba, żółw po prostu zamyka pysk i połyka zdobycz.3

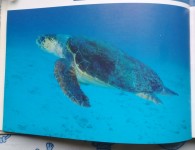

Jedynie nieliczne stworzenia morskie mogą zapuścić się powyżej granicy największego przypływu i przeżyć. Morskie żółwie zmuszone są do tego przez swój rodowód, pochodzą bowiem od lądowych żółwi oddychających powietrzem. W ciągu tysiącleci stały się wspaniałymi pływakami, zdolnymi do długiego nurkowania. Dzięki kończynom, które przekształciły się w długie i szerokie płetwy, mogą nurkować z dużą szybkością. Ale ich młode (podobnie jak potomstwo innych gadów) wy kłuwają się z jaj złożonych na brzegu. Rozwijające się zarodki żółwi do oddychania potrzebują tlenu w postaci gazu. Inaczej mogłyby się udisić i zginąć. Po kopulacji, która odbywa się w morzu, dorosłe samice żółwi opuszczają więc przyjazne wody oceanu i wychodzą na suchy ląd.

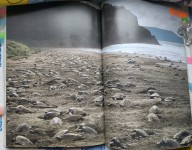

Żółwie oliwkowe, jedne z najmniejszych żółwi morskich, mierzące średnio sześćdziesiąt centymetrów długości, rozmnażają się w ogromnych skupiskach. Z pewnością jest to jeden z najbardziej zdumiewających widoków, jakie można zobaczyć, obserwując świat zwierząt. Wszystko odbywa się na jednej bądź dwóch odosobnionych plażach Meksyku i Kostaryki w ciągu kilku nocy między sierpniem a listopadem – dokładny termin trudno przewidzieć. Na plażę wychodzą z wody setki tysięcy żółwi. Żółwie te mają płuca, zaś skóra, którą otrzymały w spadku po przodkach, nie przepuszcza wody. Nie grozi im więc ani uduszenie, ani wyschnięcie. Jednakże ich płetwiaste łapy nie są przystosowane do wędrówki po lądzie. Mimo to nic nie jest w stanie ich zatrzymać. Posuwają się uparcie do przodu, aż w końcu docierają do krańca plaży, tuż przy granicy roślinności. Tam zaczynają kopać dołki na gniazda. Cała powierzchnia pokryta jest ich ciałami; leżą jeden na drugim próbując znaleźć jakieś odpowiednie miejsce. Rozgarniając łapami piasek, przysypują się wzajemnie i klepią po pancerzach. Każda samica składa w wykopanym przez siebie dołku około setki jaj, po czym ostrożnie je przykrywa i wraca do morza. Składanie jaj trwa przez trzy lub cztery noce z rzędu. W tym czasie jedną taką plażę może odwiedzić sto tysięcy żółwi oliwkowych. Po czterdziestu ośmiu dniach z jaj wylęgają się młode. Zanim to jednak nastąpi, może się zdarzyć, że ląd zalany zostanie przez drugą armię żółwi. I znów cała plaża pokrywa się pełznącymi gadami. Nowi przybysze robiąc własne dołki, nieumyślnie wykopują wiele jaj poprzedników. Dużo złożonych wcześniej jaj zostaje też zniszczonych i plaża zasłana jest ich pergaminowymi skorupkami oraz rozkładającymi się embrionami. Tylko z jednego jaja na pięćset złożonych wylęgnie się mały żółw. Reszta – zginie.

Czynniki sterujące tym masowym składaniem jaj ciągle jeszcze nie zostały dokładnie wyjaśnione. Możliwe, że wszystkie żółwie przybywają na te akurat plaże z tego prostego powodu, że właśnie w tym kierunku wiodły je prądy morskie. Możliwe jest i to, że masowe składanie jaj przez tysiące osobników w tym samym czasie jest korzystne. Gdyby bowiem wizyty żółwi na plaży odbywały się przez cały rok, mogłoby to przyciągnąć drapieżniki, takie jak kraby, węże, iguany i sępy. Kiedy natomiast wszystko odbywa się w ciągu kilku nocy, a przez większą część roku plaża nie oferuje drapieżnikom żadnych atrakcji, wtedy niewielu z nich przebywa na tej plaży w czasie, gdy zjawiają się tu żółwie. Jeśli taka jest przyczyna, to najwyraźniej przynosi ona właściwy skutek, gdyż żółwie oliwkowe są jednymi z najliczniej występujących żółwi na Pacyfiku i Atlantyku, podczas gdy liczebność innych gatunków żółwi maleje, a niektórym zagraża wyginięcie.

Największym z nich jest żółw skórzasty, który może osiągnąć ponad dwa metry długości i sześćset kilogramów wagi. Od innych żółwi różni się tym, że jego pancerz nie ma płytek rogowych, lecz tworzy go prążkowana, skórzasta, niemal elastyczna powłoka. Żółw skórzasty jest oceanicznym samotnikiem. Pojedyncze osobniki pojawiają się we wszystkich morzach tropikalnych; łapano je na południu u wybrzeży Argentyny, a na północy aż u wybrzeży Norwegii. Jeszcze dwadzieścia pięć lat temu nie było wiadomo, gdzie znajdują się główne plaże lęgowe tych zwierząt. Później odkiyto dwa takie miejsca – jedno na wschodnim wybrzeżu Malezji, a drugie – w Surinamie w Ameryce Południowej. W obu tych miejscach gniazduje jednocześnie kilka tuzinów osobników, a sezon rozrodczy trwa trzy miesiące.

Samice zwykle wychodzą na plaże nocą, gdy wzejdzie księżyc i jest wysoki przypływ. W przybrzeżnych falach, połyskując w świetle księżyca, pojawi i się ciemny garb. Uderzając wielkimi płetwiastymi kończynami, samica dźwiga w górę swe ciało, wyciągając je na mokiy piasek plaży. Co kilka minut zatrzymuje się i odpoczywa. Jej wdrapywanie się na wysokość, ku której zmierza, może trwać godzinę lub nawet dłużej. Gniazdo musi bowiem leżeć poza zasięgiem fal, ale piasek winien być wystarczająco wilgotny, żeby był zbity i nie zapadał się w czasie kopania dołu. Nim samica znajdzie właściwe miejsce, kilka razy kopie „na próbę”. Potem z dużą stanowczością zaczyna przednimi łapami wykopywać szeroki dół, odrzucając piasek za siebie. Po kilku minutach pracy dół jest wystarczająco głęboki. Możliwie najdelikatniejszymi ruchami szerokich tylnych kończyn samica wydłubuje w dnie wąskie wgłębienie. W czasie tej pracy pozostaje kompletnie głucha na dochodzące dźwięki i nawet ludzki glos nie może jej przeszkodzić. Gdyby jednak człowiek skierował na nią światło latarki w momencie wychodzenia na plażę, mogłaby zawrócić do morza nie złożywszy jaj. Ale w czasie kopania dołu nawet najostrzejsze światło już nie powstrzyma jej od złożenia jaj. Samica składa je bardzo szybko. Tylnymi kończynami ściska kloakę z obu stron i w ten sposób kieruje jaja do dołów. W czasie tej czynności samica ciężko wzdycha i stęka. Z jej ogromnych błyszczących oczu sączy się śluz. Nim upłynie pół godziny, wszystkie jaja zostają złożone, a samica napełnia dół piaskiem i ostrożnie go ugniata. Potem rzadko wraca wprost do morza. Często udaje się w inne miejsce plaży i tam kopie chaotycznie, jakby chciała zmylić trop. I rzeczywiście – zanim żółwica wróci do wody, powierzchnia plaży zostanie tak zryta, że niemożliwe jest zlokalizowanie miejsca, w którym leżą jaja.

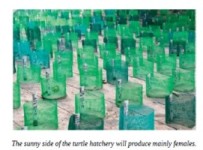

Jednak ludzie nie muszą się tego domyślać. W Malezji i Surinamie w czasie składania jaj tubylcy przez całe noce przeczesują plaże i zbierają jaja, często zanim jeszcze samica przykryje dół piaskiem. Niektóre jaja skupują lokalne agencje rządowe, aby umieścić je w sztucznych wylęgarniach. Jednak prawie cała reszta zostaje sprzedana na miejscowych targach i zjedzona.

Być może nie odkryto jeszcze wszystkich miejsc lęgowych żółwia skórzastego. Może niektóre żółwie podczas morskich wędrówek przez ocean dotarły na odosobnione bezludne wyspy, z dala od miejsc odwiedzanych przez człowieka, gdzie mogą się spokojnie rozmnażać. Żółwie nie są jedynymi stworzeniami podejmującymi dalekie wyprawy. W czasie swego dorosłego życia osobniki zamieszkujące wybrzeża nie mogą opuścić płytkich wód, ale we wcześniejszych stadiach rozwoju odbywają dalekie podróże, unoszone przez wodę podobnie jak nasiona, larwy, jaja i narybek. Dla nich wszystkich wyspa może być nie tylko jeszcze jednym domem, gdzie między wieloma mieszkańcami istnieje duża konkurencja, ale rezerwatem dającym swobodę rozwoju aż do całkiem nowych form.4

Obok dodo i drontów samotników na wyspach Mauritius, Reunion i Rodriguez żyły olbrzymie żółwie. Osiągały długość metra i wagę ponad dwustu kilogramów. Inne gatunki żółwi żyły na Komorach i na Madagaskarze. Żeglarze cenili je nawet bardziej niż dodo, bo tygodniami mogły żyć pod pokładem statku, stanowiąc żywy magazyn świeżego mięsa. Rzecz jasna, te gigantyczne żółwie spotkał ten sam los co dodo i samotniki. Pod koniec XIX wieku wszystkie wielkie żółwie na Oceanie Indyjskim zostały wyniszczone. Przeżyły tylko żółwie olbrzymie z Aldabry. Żyjąc z dala od głównych szlaków żeglugowych były tak odizolowane, że nawet ich dogodnie „opakowane” świeże mięso nie budziło w kapitanach pokusy, by zbaczać po nie z kursu. Dziś na wyspie żyje jeszcze około stu pięćdziesięciu tysięcy tych żółwi.

Wydaje się niewątpliwe, że zarówno te zwierzęta, jak i ich wymarli krewni na inn wyspach, to potomkowie żółwi normalnej wielkości żyjących na kontynencie, które wiele wiele tysięcy lat temu odbyły podróż na kępkach roślin, lądując na Madagaskarze. Jest też możliwe, że kiedyś powstała jakaś gigantyczna forma, która rozprzestrzeniła się na inne wyspy, wykorzystając w tej podróży jedynie wyporność własnego ciała.

podróż mogła się rozpocząć, gdy żółw żerujący wśród drzew mangrowych na morza został przypadkowo porwany przez falę przypływu. W przeszłości obserwowano żółwie-olbrzymy unoszące się na falach z dala od lądu. Prawdopodobnie mogą one przeżyć na morzu wiele dni. Od Madagaskaru w kierunku Aldabry płynie prąd oceaniczny, dzięki któremu żółw mógł odbyć tę trasę w ciągu dziesięciu dni.

Nie wiadomo dlaczego żółwie tworzące izolowane populacje na wyspach urosły do tak gigantycznych rozmiarów. Być może wielkiemu zwierzęciu z dużym zapasem tłuszczu łatwiej przetrwać gorszy okres niż stworzeniu o niewielkich rozmiarach. Możliwe też, że przyczyna jest prostsza. Jeśli wokół nie ma drapieżników i żadnych zwierząt konkurujących o pokarm, to stworzenia z natury długowieczne być może są w stanie osiągać większe rozmiary.

Żółwie żyjące na wyspach nie tylko osiągnęły ogromne rozmiary ciała. Zaszły w nich także inne zmiany. Na wielu takich wyspach pastwiska są rzadkością, zaś Aldabra jest pod tym względem szczególnie uboga. Nie mając wyboru, żółwie poszerzyły swój jadłospis, włączając do niego prawie wszystko, co choćby w najmniejszym stopniu nadaje się do jedzenia. Można się o tym przekonać, rozbijając na wyspie obóz. W czasie posiłków spożywanych przez obozowiczów zwierzęta te nie tylko siadają obok ludzi, ale także powoli i niezgrabnie plądrują namiot w poszukiwaniu czegoś do jedzenia. Zabierają też części odzieży pozostawione przez właściciela. Najgorsze jest jednak to, iż stały się kanibalami. Te na co dzień roślinożerne zwierzęta potrafią spożyć doczesne szczątki zmarłego krewniaka.

Zmieniły się także proporcje ciała tych żółwi. Ich ogromne pancerze nie są tak grube i mocne jak spokrewnionych z nimi żółwi z gatunków afrykańskich. Nie mają też równie silnych wewnętrznych podpór kostnych podtrzymujących pancerz. W istocie, przy niedelikatnym obchodzeniu się z pancerzem, łatwo można go uszkodzić. Taki pancerz nie daje więc bezpiecznego schronienia, jakim mogą poszczycić się żółwie kontynentalne. Przedni otwór pancerza uległ poszerzeniu i zwierzę może bardziej wysunąć się z niego na zewnątrz. Daje to żółwiowi więcej swobody podczas żerowania, ale oznacza też, że nie może on całkowicie wciągnąć swoich kończyn i szyi pod pancerz. Gdyby przenieść go z powrotem do Afryki, hieny lub szakale łatwo zacisnęłyby zęby na jego szyi.

Wszędzie na świecie żółwie tworzące na wyspach izolowane populacje uległy podobnym zmianom. Gady żyjące na Galapagos są równie duże; jednak ich najbliższymi krewniakami nie są gigantyczne żółwie z wysp Oceanu Indyjskiego, ale o wiele od nich mniejsze, żyjące w Ameryce Południowej.

Tendencja do osiągania olbrzymich rozmiarów nie ogranicza się jedynie do żółwi, ale zaznacza się i u innych gadów zamieszkujących wyspy. 5

Więc tylko jeden gatunek gigantycznej jaszczurki na Komodo, jeden olbrzymi żółw na Aldabrze i jeden gatunek dronta dodo istniał na Mauritiusie.6

Przewaga ryb w środowisku morskim nie miała jednak charakteru trwałego. Około dwustu milionów lat temu, gdy zarówno ryby o szkielecie kostnym jak i chrzęstnym występowały licznie, pewne zwierzęta zimnokrwiste, które uprzednio wykształciły już cztery kończyny i skolonizowały ląd, zaczęły wracać do morza. Gady uczyniły to pierwsze, a na ich czele znalazły się pierwotne żółwie morskie. 7

1. In normal circumstances, the frequent fast-moving fires cause little trouble to the animals. Birds can fly away from them. Ground-living creatures such as rattlesnakes and gopher tortoises take refuge for the few minutes that the fire takes to sweep by in the holes they regularly use as shelter from the oppressive midday heat.

2. Tortoises, when they get really hot – above 4o.5°C – wet their heads and neck with a great flow of saliva. Sometimes they go even further and release the large volume of liquid that they habitually store in their bladder all over their back legs.

3. The river fish are attacked by other kinds of hunters. Turtles lie in wait for them on the bottom. They are not swift swimmers and catch their prey by stealth. The matamata, a South American species, disguises itself with tatters of skin that hang from folds and dewlaps of its head and neck. Its shell, too, is uneven and often sprouts a fur of algae. When the animal lies on the bottom among rotting leaves and twigs, as it often does, it is virtually invisible. If a fish strays within range, the turtle suddenly gapes – and the fish is engulfed. The alligator snapper turtle, one of the largest of all freshwater species, growing up to 75 centimetres long, is a more active fisherman. It has a small projection on the floor of its mouth which ends in a bright red worm-like filament. It rests with its jaws agape and, every now and then, twitches its little red bait. If a fish comes to collect it, the turtle simply shuts its mouth and swallows.

4. Very few marine creatures can venture above the limit of the highest tide and survive. Turtles, however, are compelled to do so by their ancestry. They are descended from land-living, air-breathing tortoises, and have, over the millennia, become superb swimmers, able to dive beneath the surface for long periods without drawing breath, propelling themselves at great speed with legs that have been modified into long broad flippers. But their eggs, like all reptilian eggs, can only develop and hatch in air. Their developing embryos need gaseous oxygen to breathe, and without it they will suffocate and die. So every year, the adult female turtles, having mated at sea, must leave the safety of the open ocean and visit dry land. Ridleys, one of the smallest of the sea-going turtles, averaging about 60 centimetres in length, breed in vast congregations that must surely constitute one of the most astounding sights in the animal world. On one or two remote beaches in Mexico and Costa Rica, on a few nights between August and November which scientists so far have been unable to predict, hundreds of thousands of turtles emerge from the water and advance up the beach. They have the lungs and the watertight skin bequeathed them by their land-living ancestors so they arc in no danger of either suffocation or desiccation, but their flippers are ill-suited to movement out of water. But nothing stops them. They struggle upwards until at last they reach the head of the beach just below the line of permanent vegetation. There they begin digging their nest holes. So tightly packed are they that they clamber over one another in their efforts to find a suitable site. As they dig, sweeping their flippers back and fiirth, they scatter sand over one another and slap each others’ shells. When at last each turtle completes her hole, she lays about a hundred eggs in it, carefully covers it over, and returns to the sea. The laying continues for three or four nights in succession during which time over 100,000 Ridleys may visit a single beach. The eggs take forty-eight days to hatch but often before they can do so a second army of turtles arrives. Again the beach is covered with crawling reptiles. As the newcomers dig, many inadvertently excavate and destroy the eggs laid by their predecessors and the beach becomes strewn with parchment-like egg-coverings and rotting embryos. Less than one in 500 of the eggs laid on the beach survives long enough to produce a hatchling.

The factors that govern this mass breeding are still not properly understood. It may be that all the Ridleys come to these very few beaches simply because ocean currents happen to sweep them passively in that direction. It could also be advantageous for them to nest thousands at a time, since if they spaced out their visits more evenly throughout the year, the beaches would attract large permanent populations of predators such as crabs, snakes, iguanas and vultures. As it is, there is little to eat there for most of the year, so very few such creatures are there when the turtles arrive. If this is the reason for the habit, it seems to have been effective, for Ridleys in both the Pacific and the Atlantic are among the commonest of all turtles while many other species are now diminishing in numbers and some are in danger of extinction.

The biggest of them all is the leatherback turtle which can grow to over 2 metres in length and weigh 600 kilograms. It differs from all other turtles in that it has no horny plated shell but a ridged carapace of leathery, almost rubbery skin. It is a solitary ocean-going creature. Individuals may turn up anywhere in tropical seas and have been caught as far south as Argentina and as far north as Norway. Until only twenty-five years ago, no one knew where the species’ main nesting-beaches were. Then two sites were discovered, one on the east coast of Malaysia and another in Surinam in South America. On each, the leatherbacks nest, a few dozen at a time throughout a three-month season.

The females usually come at night when the moon has risen and the tide is high. A dark hump appears in the breakers, glistening in the moonlight. With strokes of her immense flippers, she heaves herself up the net sand. Every few minutes she stops and rests. It may take her half an hour or more to climb to the level she seeks, for the nest must be above the reach of the waves yet the sand must be sufficiently moist to remain firm and not cave in as she digs. She may make several trial excavations before she finally discovers a place that suits her. Then she determinedly starts clearing a wide pit with her front flippers, sweeping showers of sand behind her. After a few minutes work, it is deep enough, and with the most delicate movements of her broad back flippers, she scoops out a narrow shaft in the bottom.

She is almost entirely deaf to airborne sounds and your talking will not have disturbed her. Had you shone a torch on her as she climbed up the beach, however, she might well have turned around and gone back to the sea without laying. But now even bright lights will not stop her getting rid of her eggs. She sheds them swiftly, in groups, her back flippers clasped on either side of her ovipositor, guiding the eggs downwards. As she lays, she sighs heavily and groans. Mucus trickles from her large lustrous eyes. In less than half an hour, all her eggs are laid and she carefully tills in the pit, pressing the sand down with her hind flippers. She seldom returns directly to the sea but often moves over to other places on the beach where she digs in a desultory way, as though to confuse her trail. Certainly, by the time she heads back to the waves, the surface of the beach has been so churned up that it is almost impossible to guess just where her eggs lie.

But watching human beings need not guess. In Malaysia and in Surinam, the people patrol the beaches all night and every night during the season and collect the eggs, usually even before the females have filled in the shaft. A few eggs are now being bought by local government agencies and hatched in artificial incubators, but nearly all the rest are sold in local markets and eaten.

Perhaps we have not yet discovered all the leatherbacks’ breeding grounds. Maybe some of the turtles, as they wander through the seas, have come across remote deserted islands, far from the haunts of man, where they can breed unmolested. 'They are not the only creatures to make such voyages. Shore-living organisms are unable to move from shallow water during their adult lives; but at an earlier stage they too travel widely, floating as seeds and larvae, eggs and fry. For them all, an island may be not just another densely populated, highly competitive home like the coasts from which they have come, but a sanctuary where they can have the freedom to develop into forms that arc quite new.

5. Feeding alongside the dodos and solitaires in Mauritius, Reunion and Rodriguez were also huge tortoises. They grew to over a metre long and weighed up to 200 kilos. Others lived on the Comoro Islands and Madagascar. These were even more valuable to sailors than the dodo, for they would remain alive in the holds of ships for weeks on end, so they could provide fresh meat, even in the Tropics, many days after the ship had last left port. So the giant tortoises went the same way as the dodo and the solitaire. By the end of the nineteenth century, all the giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean had been exterminated – except for those on Aldabra. They were so isolated and so far from the main shipping routes that even the prospect of conveniently-packaged fresh meat did not tempt many captains to go so far out of their way. Today, there are still some 150,000 giant tortoises on the island.

There seems to be no doubt that they, like their extinct relatives on islands elsewhere, are descended from normal-sized tortoises living on the African mainland. It may be that some of these, many thousands of years ago, made the trip across to Madagascar riding on clumps of vegetation. It is also possible that, once giant forms developed, they spread to other islands supported by no more than the buoyancy of their own bodies.

Such voyages may well have started when a tortoise, grazing among the mangroves by the edge of the sea, was accidentally caught by the tide and swept out. Giant tortoises have certainly been found floating among the waves many miles from land and they can probably survive many days at sea. An ocean current flows from Madagascar towards Aldabra and, helped by that, a giant tortoise could make the passage in about ten days. It is by no means certain why tortoises, when isolated on islands, should become giants. Maybe a large animal, with big reserves of fat, is better able to survive a bad season than a smaller one. There may be an even simpler reason. With no predators around to attack them and no animals competing with them for the grazing, naturally long-lived creatures like tortoises may just go on growing. As well as increasing their size, the island tortoises have changed in other ways. Pasturage is not abundant on many of these islands and it is particularly scarce on Aldabra. Tortoises have consequently broadened their diet to include almost anything that is remotely edible, as you will soon discover if you camp on the island. The animals not only sit expectantly around you at mealtimes but will slowly and ponderously demolish your tent in the search for something to eat, as well as sampling any bits of your clothing that you may have left lying around. More grimly, they have also become cannibals. When one of their number dies, these normally vegetarian creatures can be seen champing their way through the dep.

The relative proportions of their bodies have also changed. Their huge shells are not as thick or as strong as those of their African relatives, nor are the internal struts of bone that support the carapace as robust. Indeed, their shells are easily dented if they are roughly handled. Nor does the carapace provide such an effective refuge as that of the mainland tortoise. The opening at the front has become wider and the animal’s body bulges farther from it. This gives the tortoise much greater freedom while browsing, but it also means that the animal is unable to withdraw its limbs and neck completely into the shell. Were it to be transported back to Africa, hyenas or jackals might well be able to fasten their teeth into the tortoise’s neck and kill it.

Tortoises on isolated islands elsewhere in the world have changed in a very similar way. There are some in the Galapagos that are equally big. Their closest relations, however, are not the giants in the Indian Ocean, but tortoises a fraction of their size that live in South America.

This tendency of island-living reptiles to grow huge is not limited to tortoises.

6. So there is only one kind of giant lizard on Komodo, one giant tortoise on Aldabra and there was only one dodo on Mauritius.

7. The fishes’ supremacy of the sea has not, however, gone unchallenged. Some 200 million years ago, when both bony and cartilaginous fish were already well-developed and numerous, some of the cold-blooded creatures that, by then, had developed four legs and colonised the land began to return to the sea. The reptiles were the first to do so when they produced the early turtles.

Autor: XYuriTT