Title: The Living Planet

Title: The Living Planet

Author(s): David Attenborough

Release year: 1984

Publisher: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd.

Why in Database: Veeeeery turtle position, we have here seven fragments, two of which are quite big. In addition, we show three turtles photos that can be found inside as well as a photo of author, David Attenborough with a leatherback turtle. The small version is from the paperback edition, and the large version is from the hardcover edition. In our databse we also have a TV series with the same title.

In normal circumstances, the frequent fast-moving fires cause little trouble to the animals. Birds can fly away from them. Ground-living creatures such as rattlesnakes and gopher tortoises take refuge for the few minutes that the fire takes to sweep by in the holes they regularly use as shelter from the oppressive midday heat.

Tortoises, when they get really hot – above 4o.5°C – wet their heads and neck with a great flow of saliva. Sometimes they go even further and release the large volume of liquid that they habitually store in their bladder all over their back legs.

The river fish are attacked by other kinds of hunters. Turtles lie in wait for them on the bottom. They are not swift swimmers and catch their prey by stealth. The matamata, a South American species, disguises itself with tatters of skin that hang from folds and dewlaps of its head and neck. Its shell, too, is uneven and often sprouts a fur of algae. When the animal lies on the bottom among rotting leaves and twigs, as it often does, it is virtually invisible. If a fish strays within range, the turtle suddenly gapes – and the fish is engulfed. The alligator snapper turtle, one of the largest of all freshwater species, growing up to 75 centimetres long, is a more active fisherman. It has a small projection on the floor of its mouth which ends in a bright red worm-like filament. It rests with its jaws agape and, every now and then, twitches its little red bait. If a fish comes to collect it, the turtle simply shuts its mouth and swallows.

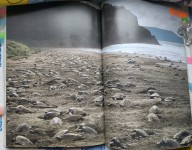

Very few marine creatures can venture above the limit of the highest tide and survive. Turtles, however, are compelled to do so by their ancestry. They are descended from land-living, air-breathing tortoises, and have, over the millennia, become superb swimmers, able to dive beneath the surface for long periods without drawing breath, propelling themselves at great speed with legs that have been modified into long broad flippers. But their eggs, like all reptilian eggs, can only develop and hatch in air. Their developing embryos need gaseous oxygen to breathe, and without it they will suffocate and die. So every year, the adult female turtles, having mated at sea, must leave the safety of the open ocean and visit dry land. Ridleys, one of the smallest of the sea-going turtles, averaging about 60 centimetres in length, breed in vast congregations that must surely constitute one of the most astounding sights in the animal world. On one or two remote beaches in Mexico and Costa Rica, on a few nights between August and November which scientists so far have been unable to predict, hundreds of thousands of turtles emerge from the water and advance up the beach. They have the lungs and the watertight skin bequeathed them by their land-living ancestors so they arc in no danger of either suffocation or desiccation, but their flippers are ill-suited to movement out of water. But nothing stops them. They struggle upwards until at last they reach the head of the beach just below the line of permanent vegetation. There they begin digging their nest holes. So tightly packed are they that they clamber over one another in their efforts to find a suitable site. As they dig, sweeping their flippers back and fiirth, they scatter sand over one another and slap each others’ shells. When at last each turtle completes her hole, she lays about a hundred eggs in it, carefully covers it over, and returns to the sea. The laying continues for three or four nights in succession during which time over 100,000 Ridleys may visit a single beach. The eggs take forty-eight days to hatch but often before they can do so a second army of turtles arrives. Again the beach is covered with crawling reptiles. As the newcomers dig, many inadvertently excavate and destroy the eggs laid by their predecessors and the beach becomes strewn with parchment-like egg-coverings and rotting embryos. Less than one in 500 of the eggs laid on the beach survives long enough to produce a hatchling.

The factors that govern this mass breeding are still not properly understood. It may be that all the Ridleys come to these very few beaches simply because ocean currents happen to sweep them passively in that direction. It could also be advantageous for them to nest thousands at a time, since if they spaced out their visits more evenly throughout the year, the beaches would attract large permanent populations of predators such as crabs, snakes, iguanas and vultures. As it is, there is little to eat there for most of the year, so very few such creatures are there when the turtles arrive. If this is the reason for the habit, it seems to have been effective, for Ridleys in both the Pacific and the Atlantic are among the commonest of all turtles while many other species are now diminishing in numbers and some are in danger of extinction.

The biggest of them all is the leatherback turtle which can grow to over 2 metres in length and weigh 600 kilograms. It differs from all other turtles in that it has no horny plated shell but a ridged carapace of leathery, almost rubbery skin. It is a solitary ocean-going creature. Individuals may turn up anywhere in tropical seas and have been caught as far south as Argentina and as far north as Norway. Until only twenty-five years ago, no one knew where the species’ main nesting-beaches were. Then two sites were discovered, one on the east coast of Malaysia and another in Surinam in South America. On each, the leatherbacks nest, a few dozen at a time throughout a three-month season.

The females usually come at night when the moon has risen and the tide is high. A dark hump appears in the breakers, glistening in the moonlight. With strokes of her immense flippers, she heaves herself up the net sand. Every few minutes she stops and rests. It may take her half an hour or more to climb to the level she seeks, for the nest must be above the reach of the waves yet the sand must be sufficiently moist to remain firm and not cave in as she digs. She may make several trial excavations before she finally discovers a place that suits her. Then she determinedly starts clearing a wide pit with her front flippers, sweeping showers of sand behind her. After a few minutes work, it is deep enough, and with the most delicate movements of her broad back flippers, she scoops out a narrow shaft in the bottom.

She is almost entirely deaf to airborne sounds and your talking will not have disturbed her. Had you shone a torch on her as she climbed up the beach, however, she might well have turned around and gone back to the sea without laying. But now even bright lights will not stop her getting rid of her eggs. She sheds them swiftly, in groups, her back flippers clasped on either side of her ovipositor, guiding the eggs downwards. As she lays, she sighs heavily and groans. Mucus trickles from her large lustrous eyes. In less than half an hour, all her eggs are laid and she carefully tills in the pit, pressing the sand down with her hind flippers. She seldom returns directly to the sea but often moves over to other places on the beach where she digs in a desultory way, as though to confuse her trail. Certainly, by the time she heads back to the waves, the surface of the beach has been so churned up that it is almost impossible to guess just where her eggs lie.

But watching human beings need not guess. In Malaysia and in Surinam, the people patrol the beaches all night and every night during the season and collect the eggs, usually even before the females have filled in the shaft. A few eggs are now being bought by local government agencies and hatched in artificial incubators, but nearly all the rest are sold in local markets and eaten.

Perhaps we have not yet discovered all the leatherbacks’ breeding grounds. Maybe some of the turtles, as they wander through the seas, have come across remote deserted islands, far from the haunts of man, where they can breed unmolested. ‘They are not the only creatures to make such voyages. Shore-living organisms are unable to move from shallow water during their adult lives; but at an earlier stage they too travel widely, floating as seeds and larvae, eggs and fry. For them all, an island may be not just another densely populated, highly competitive home like the coasts from which they have come, but a sanctuary where they can have the freedom to develop into forms that arc quite new.

Feeding alongside the dodos and solitaires in Mauritius, Reunion and Rodriguez were also huge tortoises. They grew to over a metre long and weighed up to 200 kilos. Others lived on the Comoro Islands and Madagascar. These were even more valuable to sailors than the dodo, for they would remain alive in the holds of ships for weeks on end, so they could provide fresh meat, even in the Tropics, many days after the ship had last left port. So the giant tortoises went the same way as the dodo and the solitaire. By the end of the nineteenth century, all the giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean had been exterminated – except for those on Aldabra. They were so isolated and so far from the main shipping routes that even the prospect of conveniently-packaged fresh meat did not tempt many captains to go so far out of their way. Today, there are still some 150,000 giant tortoises on the island.

There seems to be no doubt that they, like their extinct relatives on islands elsewhere, are descended from normal-sized tortoises living on the African mainland. It may be that some of these, many thousands of years ago, made the trip across to Madagascar riding on clumps of vegetation. It is also possible that, once giant forms developed, they spread to other islands supported by no more than the buoyancy of their own bodies.

Such voyages may well have started when a tortoise, grazing among the mangroves by the edge of the sea, was accidentally caught by the tide and swept out. Giant tortoises have certainly been found floating among the waves many miles from land and they can probably survive many days at sea. An ocean current flows from Madagascar towards Aldabra and, helped by that, a giant tortoise could make the passage in about ten days. It is by no means certain why tortoises, when isolated on islands, should become giants. Maybe a large animal, with big reserves of fat, is better able to survive a bad season than a smaller one. There may be an even simpler reason. With no predators around to attack them and no animals competing with them for the grazing, naturally long-lived creatures like tortoises may just go on growing. As well as increasing their size, the island tortoises have changed in other ways. Pasturage is not abundant on many of these islands and it is particularly scarce on Aldabra. Tortoises have consequently broadened their diet to include almost anything that is remotely edible, as you will soon discover if you camp on the island. The animals not only sit expectantly around you at mealtimes but will slowly and ponderously demolish your tent in the search for something to eat, as well as sampling any bits of your clothing that you may have left lying around. More grimly, they have also become cannibals. When one of their number dies, these normally vegetarian creatures can be seen champing their way through the dep.

The relative proportions of their bodies have also changed. Their huge shells are not as thick or as strong as those of their African relatives, nor are the internal struts of bone that support the carapace as robust. Indeed, their shells are easily dented if they are roughly handled. Nor does the carapace provide such an effective refuge as that of the mainland tortoise. The opening at the front has become wider and the animal’s body bulges farther from it. This gives the tortoise much greater freedom while browsing, but it also means that the animal is unable to withdraw its limbs and neck completely into the shell. Were it to be transported back to Africa, hyenas or jackals might well be able to fasten their teeth into the tortoise’s neck and kill it.

Tortoises on isolated islands elsewhere in the world have changed in a very similar way. There are some in the Galapagos that are equally big. Their closest relations, however, are not the giants in the Indian Ocean, but tortoises a fraction of their size that live in South America.

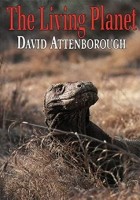

This tendency of island-living reptiles to grow huge is not limited to tortoises.

So there is only one kind of giant lizard on Komodo, one giant tortoise on Aldabra and there was only one dodo on Mauritius.

The fishes’ supremacy of the sea has not, however, gone unchallenged. Some 200 million years ago, when both bony and cartilaginous fish were already well-developed and numerous, some of the cold-blooded creatures that, by then, had developed four legs and colonised the land began to return to the sea. The reptiles were the first to do so when they produced the early turtles.

Author: XYuriTT